This is the second installment of the “Complexity Series,” where I endeavor to argue that there are certain classes of problems (simple arithmetic being one of them) that Transformer architectures will never be able to solve.

In my previous post, I outlined that we have thus far discovered a few algorithms that are being implicitly implemented by LLMs to perform arithmetic (regular or modulo):

- The “Clock” algorithm (Kantamneni and Tegmark), covered in my previous post, “LLM Arithmetic”

- Bag of Heuristics (Nikankin et. al, Anthropic)

- Digit-wise and Carry-over Circuits (Quirke and Barez)

These represent a good coverage of classes of algorithms that LLMs have learnt. While my previous post focuses on the “Clock” method and illustrates extremely mechanistically how the clock method performs modulo arithmetic, this post will focus on the last method written about by Quirke and Barez. By the end of this post, we will have established an understanding of how this algorithm works, and what its limitations are.

1. How Would You Do Arithmetic?

Let’s do a simple thought experiment focusing on the complexity (think Kolmogorov Complexity) of doing addition. How would you specify a way of adding 2 numbers as succinctly as possible?

For adding single digit numbers, it’s simple - memorization table:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

This express the ENTIRETY of single digit addition. The requires storing $10 \times 10 = 100$ values. For double-digit addition, we could do the same, but we’d end up storing $100 \times 100 = 1,000$ values, not great, and indeed, this is memorization, not learning addition. Let’s do better.

The way we learned (I did, not sure about you 🙂) to do arithmetic at a young age is quite succinct to me.

- Right-justify the 2 numbers and stack them on top of each other to align the digits

- For each digit from right to left, we perform single-digit arithmetic (i.e. look up the above table). If the answer has 2 digits, take only the digit in the ones place. Let’s call this “naive single-digit addition,” aka “Base Add”, which we will introduce later. Also, remember you have to carry 1 over.

- Move to the next column, and perform the same single-digit arithmetic. If you had to carry 1 over from the previous column, perform single-digit arithmetic again with $1$.

The 3rd step above has a few implementations. You could either choose to implement single-digit arithmetic with 200 parameters (one $10 \times 10$ lookup table for single-digit arithmetic, with and without carrying 1 over from before), or you could just always perform single-digit arithmetic twice (one for the original digits in that column, and one more between the result of that and either $1$ or $0$, depending if there was a carry-over 1 from before).

Regardless, this is a sufficient expression of the problem solution that can work for ANY number of digits of arithmetic, and it works with just 200 parameters and 3 lines of instruction. If, given this solution description, you can’t implement it, then either you don’t have enough storage space to store the 200 parameters, or you don’t understand how to implement the 3 lines of instructions, and indeed, the 3 lines contain actions that are not obvious to encode in LLM circuits, and are the root of why certain classes of problems are impossible to solve with today’s LLMs:

- Right-justify: that said, there’s ongoing research on how models cope with spatial requirements like these, and I am sufficiently convinced for now that this is not an unsolvable problem.

for each: this is the really hard one.

2. Algorithm Summaries

2.1 Quirke and Barez

This human method of performing addition constitutes the framework that Quirke and Barez use to reason out what a model that knows how to perform addition MUST be able to do. They introduce these terms for the above described steps:

- “Base Add (BA),” which “calculates the sum of two digits $D_i$ and $D’_i$ modulo $10$, ignoring any carry over from previous columns” - we called this naive single-digit addition.

- “Make Carry 1 (MC1),” which “evaluates if adding digits $D_i$ and $D’_i$ results in a carry over of $1$ to the next column.”

And there’s also a third computation - “Make Sum 9 (MS9),” that evaluates if $D_i + D’_i = 9$ exactly. This is an important feature because if both MS9 and MC1 are active, then the model needs to know to propagate the carry 1 to the next column. They call these receptor components Use Carry 1 (UC1) and Use Sum 9 (US9). For succinctness, we’ll assume that whenever there’s a MS9, there’ll be a corresponding US9, and same for MC1 and UC1. This way, we’ll only have to mention MS9 and MC1.

Interesting Claim 1: The Model Only Looks At 3 Digits Per Digit

The authors claim that “the model has slightly different algorithms for the first answer digits, the middle answer digits, and the last answer digits,” where:

- “First answer digits” refer to the digit in the most significant digit position (the 10,000’s column in a 5 digit addition task), AND the digit to the left (in case the addition gives a 6-digit answer).

- “Last answer digits” refer to the digits in the 1’s and 10’s column (we’ll see why these are different from the “middle digits”).

- “Middle digits” refer to everything else in the middle.

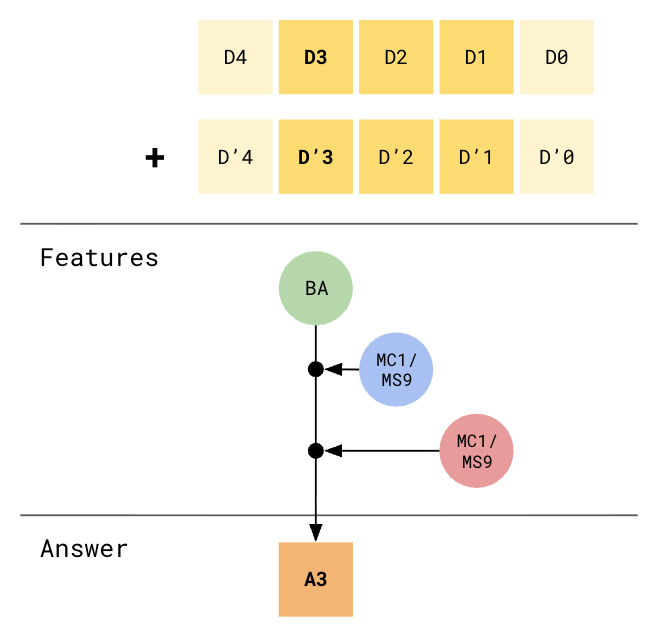

This claim stems from the analysis that middle digits (most complex) need to use 3 digits (itself and its 2 right-ward neighbors) to compute their result:

Computing A3 needs features from positions 1, 2, and 3

Computing A3 needs features from positions 1, 2, and 3

Interpreting the graph: I’ve also color-coded the feature computations by which attention head is computing those features. So, one head is responsible for computing MC1 on position_1, one head is responsible for computing MC1 and MS9 on position_2 (at most one can be true, so this can basically be treated as the same set of category features), and another head is responsible for computing BA on position_3. Then, the MLP block performs a trigram lookup for this combination of BA (green head), MC1/MS9 (blue head), MC1/MS9 (red head), and arrives at the answer for position_3.

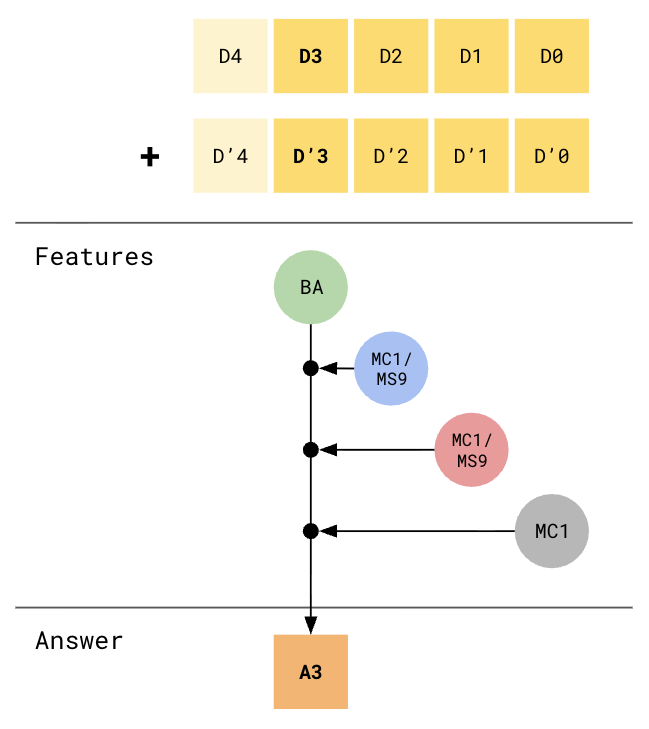

So this algorithm is not entirely correct / robust to me, because what if position_1.MC1 was not active, but position_1.MS9 and position_0.MC1 were? In English, that meant that a carry-1-over was propagated all the way from position 0. This propagation can happen for any number of contiguous positions, so just looking at 3 digit positions is insufficient. They confirm this later by saying “this algorithm explains all the observed prediction behaviour - including the fact that the model can calculate a simple US9 case but not a cascading US9 case.”

Interesting Claim 2: MLP is encodes a Trigram Lookup

The authors say that the MLP can be thought of as a “key-value pair” memory that can hold many bigrams and trigrams. Basically, the combination of the 3 feature states above:

position_3.BA: 10 possible statesposition_2.MC1: 2 possible statesposition_2.MS9ANDposition_1.MC1: 3 possible states (I disagree; this can be thought of as either a 2-state (logical AND functions have binary outcomes) or 4-state function (any combination of these 2 sub-features)).

will give a total of $10 \times 2 \times 3 = 60$ possible outcomes. They claim: “For each digit, the MLP has memorised the mapping of these 60 keys to the 60 correct digit answers (0 to 9). We haven’t proven this experimentally. Our MLP is sufficiently large to store this many mappings with zero interference between mappings.” These are unsurprising claims, but I would have loved to see the features being extracted out from the MLP space using simple visualization techniques such as the one I introduced in “Superposition - An Actual Image of Latent Spaces”.

Interesting Claim 3: Model Waits Till seeing = Before Computing

The authors also claim that “despite being feasible, the model does not calculate the task MC1 in rows 7 to 11. Instead, it completes each answer digit calculation in 1 row, possibly because there are training optimisation benefits in generating a “compact” algorithm.” I claim that the predominant reason it does not calculate MC1 (and BA for that matter) before row 12 (when the = token has been seen) because it has no incentive to. Before row 12, the job of the model is not to perform addition. In fact, it is being trained to predict the rest of the question, which is entirely orthogonal to the task of addition.

Rabbithole: If one postulates that perhaps the model has some incentive to pre-emptively add tokens 1 and 7 (the first digits of both numbers) before row 12, then one must also postulate that perhaps the model has some incentive to add tokens 1 and 8, tokens 1 and 9, tokens 1 and 10, and basically every pair of tokens, because prior to seeing the

=, the model has no idea what lengths the 2 numbers have, and hence how to line up the 2 numbers to do addition. That said, I recognize that if a model that has specifically been fine-tuned to do $n$-digit addition could perhaps figure out that if it were to dedicate some attention-heads to pre-emptively compute and cache the MC1 and BA1 values for the relevant token pairs (1, 7), (2, 8), etc…, then this cache could be picked up later on to better handle some of the more extended cascading MS9 / US9 cases.

Their Conclusions

Through varying the expected format of the result (e.g. +54321 instead of 54321) and carrying out similar ablation experiments to identify attention heads performing BA, MC1, and MS9, they suggest that “the transformer architecture, when trained on the addition task, converges to a consistent algorithm for performing digit-wise addition.” I think their analysis of the computation components is insufficiently mechanistic for me, but this won’t be the focus of this post. For the sake of further argumentation, I’ll simply believe their claims.

Limitations

As they’ve correctly identified, cases were there are cascading MS9 / US9’s are problematic for this 1-layer transformer. In fact, this algorithm demonstrates a weakness that generalizes to transformers of any number of attention heads and lengths, provided that that number is finite. Let’s see why.

To be able to handle length-$k$ cascades of MS9 with this algorithm of computation, there are 3 ways to increase $k$: increasing the number of attention heads, increasing the length of the model, and increasing the numbers of digits represented in a single token.

More Attention Heads:

1 more attention head allows us to also consider position 0, but MLP must encode quadrigrams now

1 more attention head allows us to also consider position 0, but MLP must encode quadrigrams now

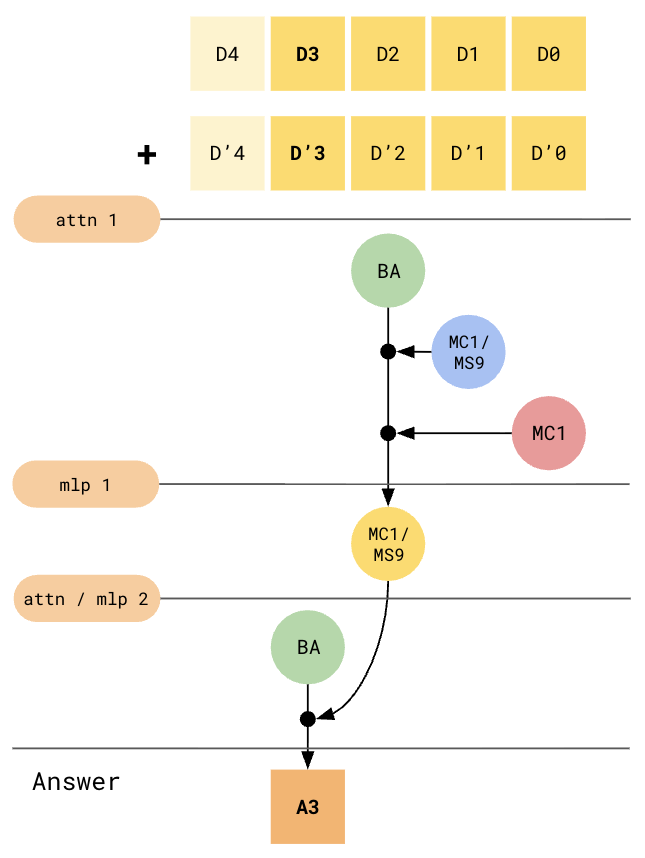

More Transformer Blocks:

Splitting carry computations across transformer blocks makes this scale with model depth

Splitting carry computations across transformer blocks makes this scale with model depth

A transformer could definitely learn to use both strategies, but essentially, $k$ can only scale linearly with num_layers + num_attention_heads_per_layer. This algorithm that the transformer has learnt certainly does not encapsulate the for each aspect of an addition algorithm. This is akin to how a compiler without a jump_equal / jump_not_equal instruction can only produce loops that run a static number of times, because the compiler has no choice but to unfurl all iterations of the loop and duplicate the within-loop logic however many times the loop was intended to run.

Bigger Tokens:

This is less interesting to me so I’ll just briefly describe it. Thus far, we’ve treated every unique single-digit as a token, so there are 10 of them. Our memorization table was hence $10 \times 10 = 100$ entries large. This memorization table can be implemented as a bigram lookup table in the MLP block, so the implication here is that if your MLP is more expressive, you could also encode every unique double-digit as a token, so you would have a total of 100 tokens, which would necessitate a memorization table with $100 \times 100 = 10000$ entries. This would basically halve the required depth of your LLM in order to be able to perform arithmetic properly on $n$-digit long numbers, since the number comprises half the number of tokens.

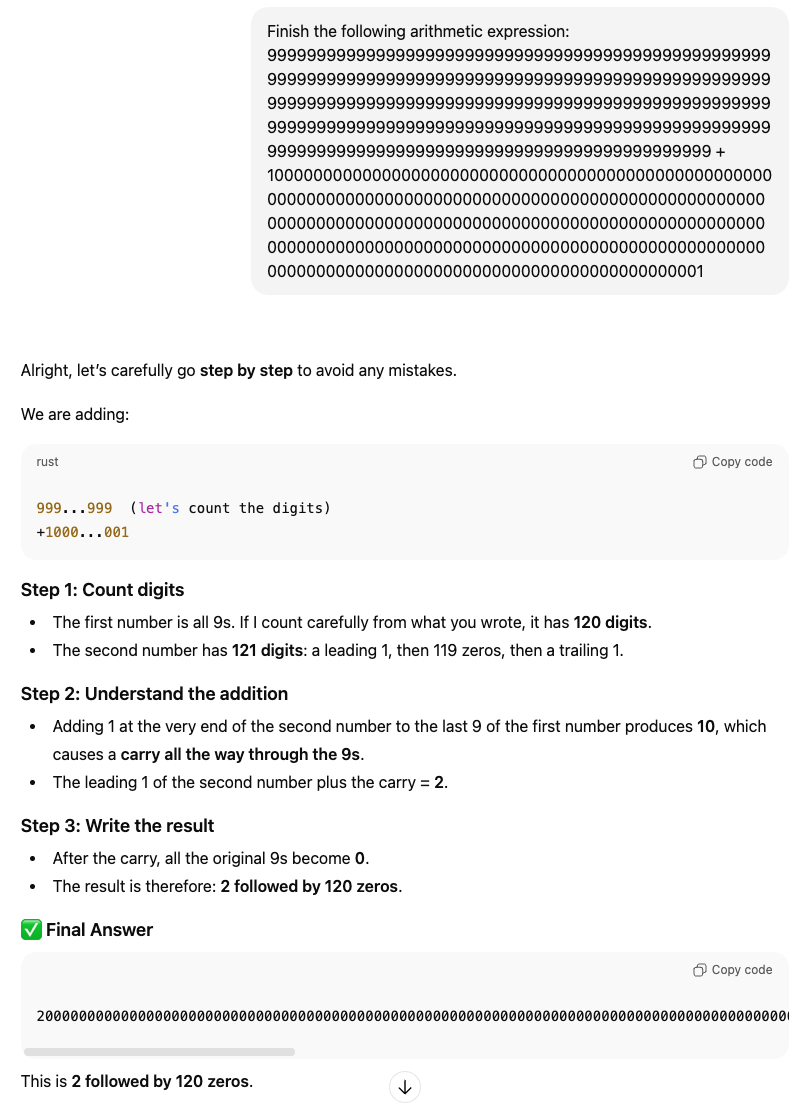

In reality, LLM tokenizers do actually have tokens corresponding to double-digits, triple-digits, and more, since these are really common in training corpora. This is also the reason LLMs like ChatGPT (as of 2026) still trip up on simple counting tasks:

249-digit number + 250-digit number

249-digit number + 250-digit number

Above shows my conversation with ChatGPT, where I asked it to add a string of 249 9’s and a 250-digit number starting and ending with 1. The first interesting observation is that it thinks that the numbers have 120 and 121 digits respectively, and while I cannot confirm mechanistically that this is due to the tokenization (nor do I care, really), it is a rather plausible explanation.

The second interesting observation is that it did not get the answer right. Since you can’t see the full code, you’ll have to just take my word for it (🤷) that ChatGPT’s answer was this:

1

200000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Which is missing 1 zero. This observation is interesting but not particularly insightful because ChatGPT (as well as other LLM providers) now operate in the thinking framework, where the answers presented are not the generations that are sampled right out the model, but answers that have been given after some amount of intermediate “thinking tokens” have been generated. In this case, those thinking tokens (the visible ones anyway, there are most definitely more of them that are invisible to consumers) are “Alright, let’s carefully go step by step to avoid any mistakes […].” This crowdsources the computation to various shards (i.e. sub-circuits) that each perform a bunch of various actions that are not generalizable. In this case it seems:

- a shard responsible for recognizing number patterns like “a string of $n$

9s” is activated and that triggers a totally different arithmetic computation pathway that is not performing the mechanical algorithm but doing a shortcut that is specifically applicable to this pattern (and is hence not generalizable). We can see this happening in the first bullet point of Step 2.

In essence, it seems that these shards are often just implementing heuristics. In the next post, we will see that LLMs are also able to end up learning very strong heuristics-based algorithms, where the heuristics patch together a surprisingly good coverage of input domains to be able to smoke its ability to perform a certain task; stay tuned!

TLDR, we know that the LLM has not learnt a generalizable algorithm for arithmetic.

Aside: While thinking step-by-step is useful, I think it is in general philosophically not the right way to augment the capabilities of LLMs. “Thinking step-by-step” is just LLM parlance for crapping out more tokens, which are the subtrate of LLM computation. My intuition for this is it that expanding the substrate space also expands the space of possible outputs that the LLM can consider, and hence the variance of model performance is generally smaller. I’m not convinced that it meaningfully augments the expressive capability of LLMs, and if anything, this extended self-hallucination makes models harder to control and interpret.

Conclusion

While the Carry-over Circuit elucidated by Quirke and Barez does seem like a principled way to perform arithmetic that also mirrors the traditional way people hand-perform arithmetic, we see that there are blatant limitations in the way this circuit can be expressed within the LLM’s architecture that severely limit the size of the numbers that arithmetic can be performed on.