Can we build a zero-shot Large Language Model (LLM) generated text detector without knowing which LLM potentially generated a given piece of text?

A Stanford NLP research project (CS 224N) done in collaboration with Raghav Garg. Contact me for more information!

Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Related Work

- Approach

- Results

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Appendix

1. Abstract

The rapidly advancing capabilities and application of Large Language Models (LLMs) for text generation emphasize the increasing need to investigate the nature of and distinguish synthetic texts from human texts, for both practical and theoretical purposes. While supervised and non-supervised approaches have been previously explored and remain of interest, we focus on non-supervised approaches as they don’t require intensive compute associated with supervised approaches and have the potential to reason about the characteristics of synthetic text regardless of which model generated them. The most performant zero-shot (i.e. does not require further fine-tuning) approach so far remains DetectGPT, but it is reliant on having access to the Source Model that potentially generated the text in question.

We explore a novel zero-shot approach to distinguishing LLM text from human text that uses an existing LLM (e.g. GPT-2), but that does not rely on having access to, or even knowledge of the source model, beyond a loose assumption that the source model looks somewhat like a Transformer. The approach is based on the hypothesis that human texts are less “uniform” than LLM-generated texts; if we were to segment a given text into partitions of more or less equal size, and evaluate some metric of “GPT-2-ness” (or the equivalent of whatever model is used in our approach) of each partition, if the text were synthetic, then this measure of “GPT-2-ness” will be much more consistent (uniform) across partitions than if the text were human-generated.

We find that our method gives weak performance, making this not the discriminator of choice, with a few exceptions such as when the text-generating model is sufficiently different than any available scoring model. Moreover, and more interestingly, we show that human text is not only less “optimal” in the model-defined sense, but also often has consistent levels of optimality (or sub-optimality), and such consistency is comparable to the consistency of the optimality of LLM-generated texts.

2. Introduction

Models such as OpenAI’s GPT-3 and Google’s LaMBDA have demonstrated the ability to generate impressively coherent and on-topic texts across various domains, from education, to healthcare, to engineering. While they can be immensely useful, they can also be destructively used to complete student assessments, create and propagate fake-news articles, spam, and scams, provide misleading or false information (intentionally or not); these deleterious use-cases extend wherever the use of LLMs is of relevance. Methods to detect LLM-generated text can be immensely useful in guiding fruitful use of LLMs, be it as a tool to filter spam, a cheating detection mechanism, or even just a sanity check on the trustworthiness of a piece of text. Though there are many reasons to have a computational approach to LLM-generated text detection - and these have been widely discussed and agreed upon - the chief concern is that humans have been demonstrated to be only slightly better than chance at identifying LLM-generated text (Gehrmann et al.) This advantage will only deteriorate as LLMs continue to improve.

Current methods can be broadly categorized into supervised approaches, wherein a pretrained LLM is fine-tuned on the specific task of classifying texts into “LLM” or “human”-generated, as well as non-supervised approaches, wherein white-box methods such as the thresholding of statistical measurements like entropy are used to accuse a piece of text as LLM-generated (Gehrmann et al.). Non-supervised / zero-shot approaches are particularly interesting because they don’t need compute-intensive fine-tuning, are not susceptible to training data biases in the ways that supervised approaches typically are, and also because they have the potential to reveal interpretable characteristics about the nature of LLM-generated texts, in comparison to human-written ones.

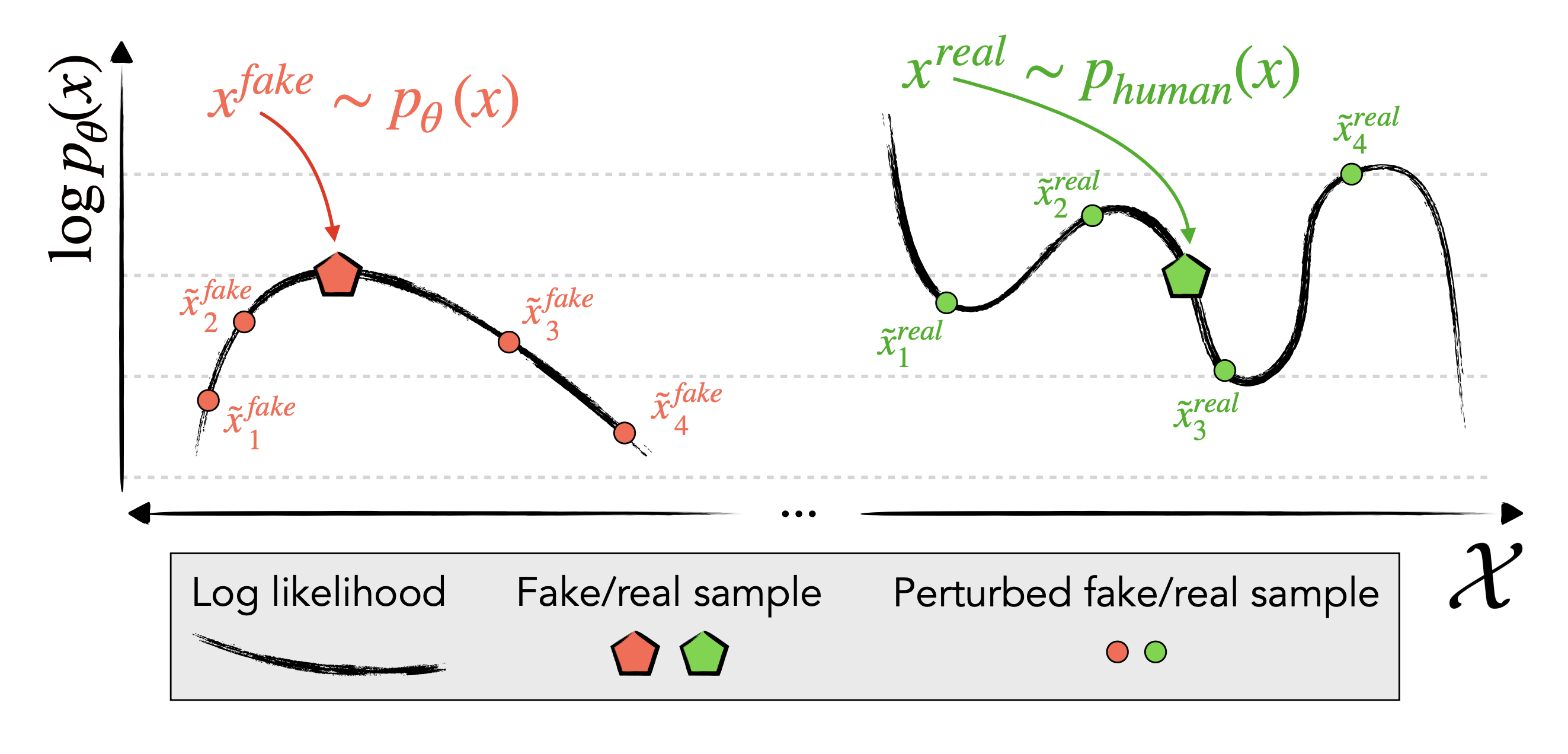

Zero-shot approaches typically rely on statistical features; as a result, the challenge is in extracting as much signal as possible that could discriminate a piece of text between LLM and human-generated. Earlier methods have relied on thresholding some measure based on the model’s assessment of word / token log-probabilities (e.g. average log-probabilities, word likelihood ranking, entropy, etc.), but those “absolutist” methods are inherently constrained in performance because it fails for texts that contain predominantly high-probability or low-probability words (due to the nature of the content) because both LLM and human-generated texts will be high or low-probability respectively. Other improvements, most notably DetectGPT, address this issue by using an LLM to sample random perturbations of the text - variants of the original text, but with some tokens swapped out in exchange for different sampled tokens - and comparing the discrepancy between the mean perturbation likelihood and the original text likelihood, as measured by yet another LLM (the scoring LLM). Because this derives from the idea that LLM-generated text is more “relatively optimal” than their local neighborhood of texts than human-generated text, it normalizes for the text’s inherent likelihood.

Above (from DetectGPT): an illustration of a text's log-likelihood relative to perturbations of it in a hidden "semantic space".

DetectGPT is a large conceptual improvement and performs extremely well when the \textit{scoring LLM} is the same as the source LLM (the LLM that was used to generate the text, if it was LLM-generated at all), but performance drops off considerably if they differ, which we may intuit as due to probability-scoring discrepancies between models. Given the proliferation of LLMs, it is increasingly impractical to have different detecting models watching out for different specific source models, or even to know what the source model is, such as when it is proprietary.

We introduce a method based on the hypothesis that LLM writing is more “uniform” than human writing. We investigate the consistency of a statistical measure (which we define later) across different parts of a text, with the hypothesis that this statistic will vary significantly more across the different partitions of a single piece of text if it’s human-written, compared to if it’s LLM-generated. Because we look at the within-text variance of this statistical measure as computed by an LLM of choice, rather than the mean, probability-scoring discrepancies between our chosen scoring LLM and the source LLM could not matter as much. This “second-order” approach could do away with the need for access or even knowledge to the very source LLM that we would like to detect.

3. Related Work

Zero-shot approaches have been thus far considerably well explored, with many of the earlier methods relying on the idea that LLMs have been optimized to generate “convincing”-looking text. Specifically, words (or tokens), which are generated have high likelihood of appearing in their respective contexts, are constrained to be one of the $k$ most-probable possible words the LLM could choose at that spot in the text (Ippolito et. al) and have lower entropy (Gehrmann et al.), and so on. These methods suffer from being “absolutist,” as mentioned in Section 2. DetectGPT improves on the flaw of these “zeroth-order” approaches by incorporating information from the “local structure of the learned probability function around a candidate passage,” in a sense comparing a text’s probability of occurring to the mean of that of any of the possible nearby variants (perturbations) of the text. Their technique is also more nuanced as it incorporates the finding that the probability curvature at LLM-generated texts tends to be negative while that of human-written texts does not.

While they present a major conceptual and performance improvement with the use of a “first-order” approach, DetectGPT keeps the soft requirement of knowing and using the very same LLM that one wishes to watch out for. One may intuit this to be due to the discrepancies in probability scores between different models. One LLM’s assessment of probability curvature at a point may well be different from another’s at the same point, and by extension, so are their probability distributions.

We extend the idea of surveying the model’s probability function in the neighborhood of a text as presented in DetectGPT, and empirically studying additional information that may exist in the relationship between the characterization of said neighborhoods of various partitions of a text.

4. Approach

For a piece of text $x$, we first segment it into partitions of about $50$ tokens, to produce partitions $x^{(j)}, j \in [1, p]$, where $p =$ number of partitions for this text.

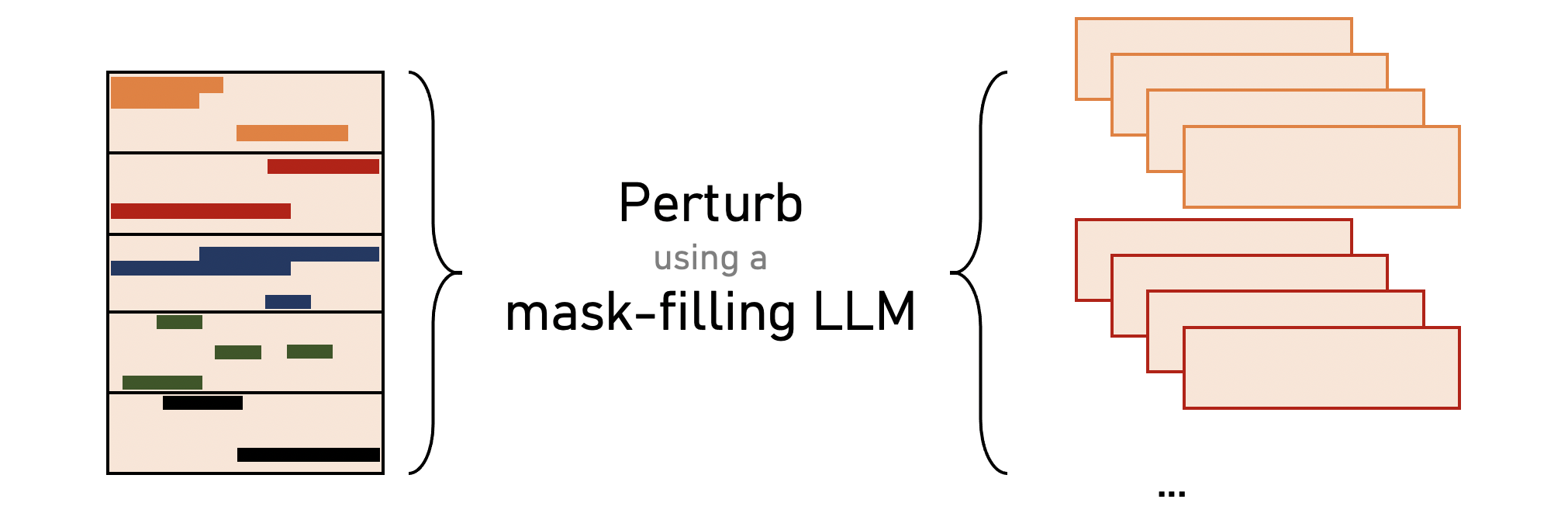

We then We then generate $50$ perturbations $\tilde{x}^{(j,k)}, k \in [1, 50]$ of each partition by randomly selecting $15\%$ of words to mask out and fill in with sampled generations from a mask-filling LLM.

![perturb]()

We then score the log-likelihoods of all the perturbed partitions as well as the original partitions using a scoring LLM such as GPT-2, denoting a log-likelihood by $\log p_\theta (\cdot)$.

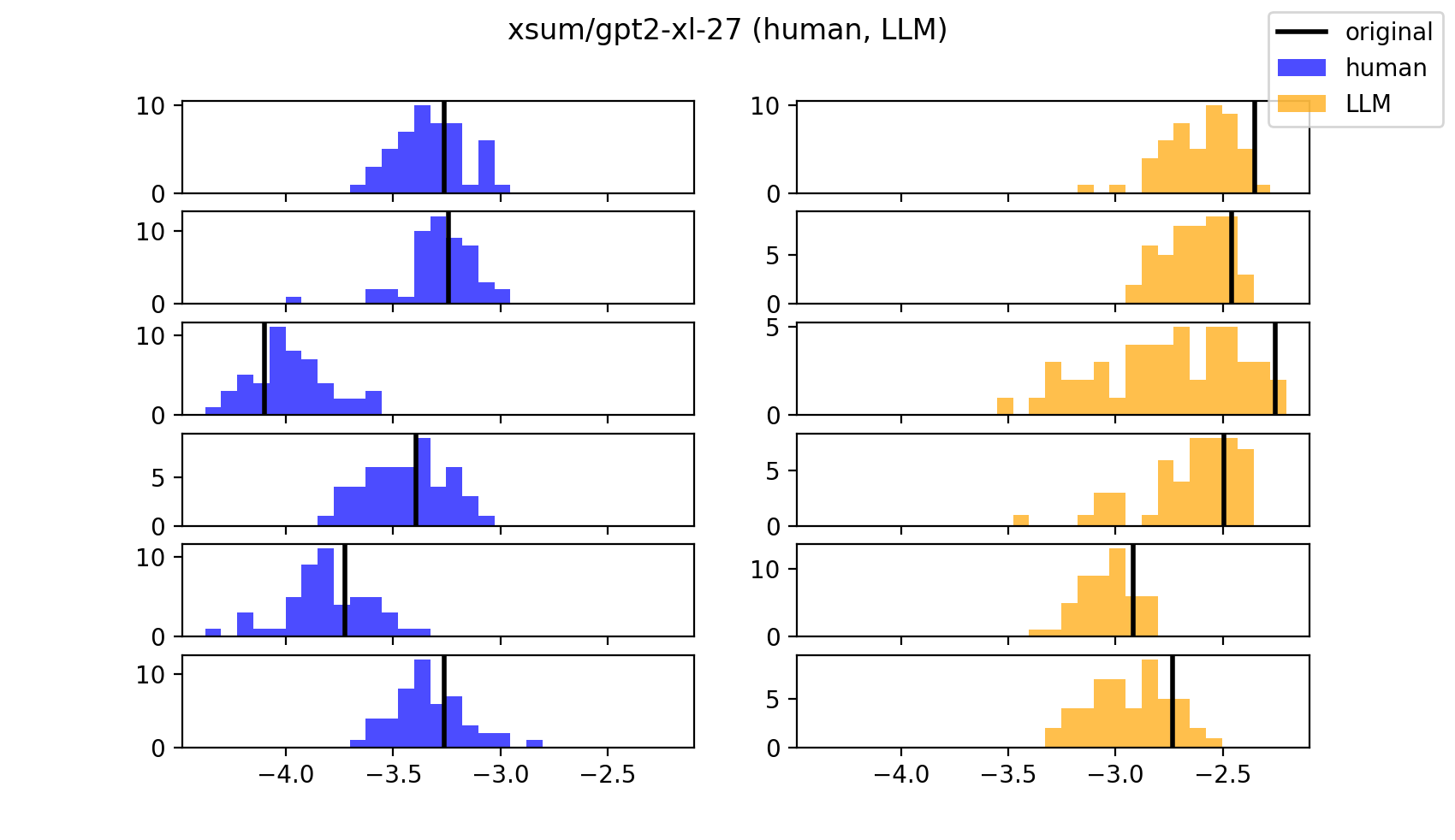

![sample segment Z-scores]()

Above: each histogram is of a partition’s perturbed log-likelihoods. The black line is the original partition’s log-likelihood.Similar to DetectGPT, we approximate these perturbation log-likelihood distributions to Gaussian Distributions (i.e. $\log p_\theta(\cdot) \sim \mathcal{N}(\cdot,\cdot)$), and record the Z-score of each original partition’s log- likelihood (henceworth referred to as simply “Z-score”) with respect to its distribution of perturbed log-likelhoods.

We then calculate the variance of the partition-specific Z-score, for the piece of text. In our experiments, each text has a human-written and a LLM-generated equivalent, so we calculate the variance for both:

- $\sigma^2_{Z, human}$

- $\sigma^2_{Z, LLM}$

As per our hypothesis, if, within a piece of text, across its partitions, the variance of partition Z-scores is high, then we believe it was written by a human. In notation, our hypothesis can be writen as:

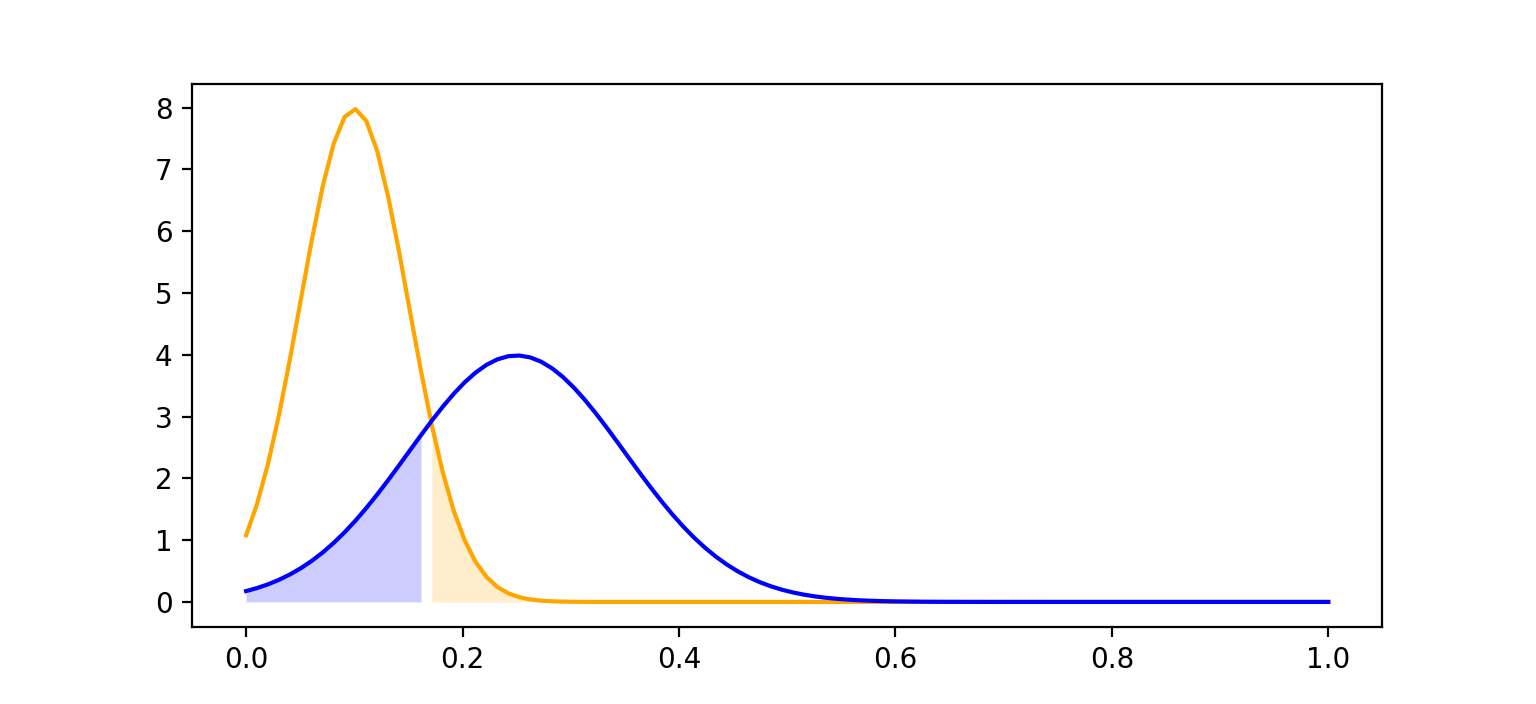

\[\sigma^2_{Z,human} > \sigma^2_{Z,LLM}\]Graphically, we hope that the distribution of $\sigma^2_{Z,author}$ (where $author \in [human, LLM]$) turns out to look like the following, where the blue curve is the human variance, and the orange curve is the LLM variance. The shaded regions correspond to False Positive Rate and False Negative Rate.

The metric we use to determine the efficacy of our method is the AUROC score using these $\sigma^2_{Z,author}$

5. Results

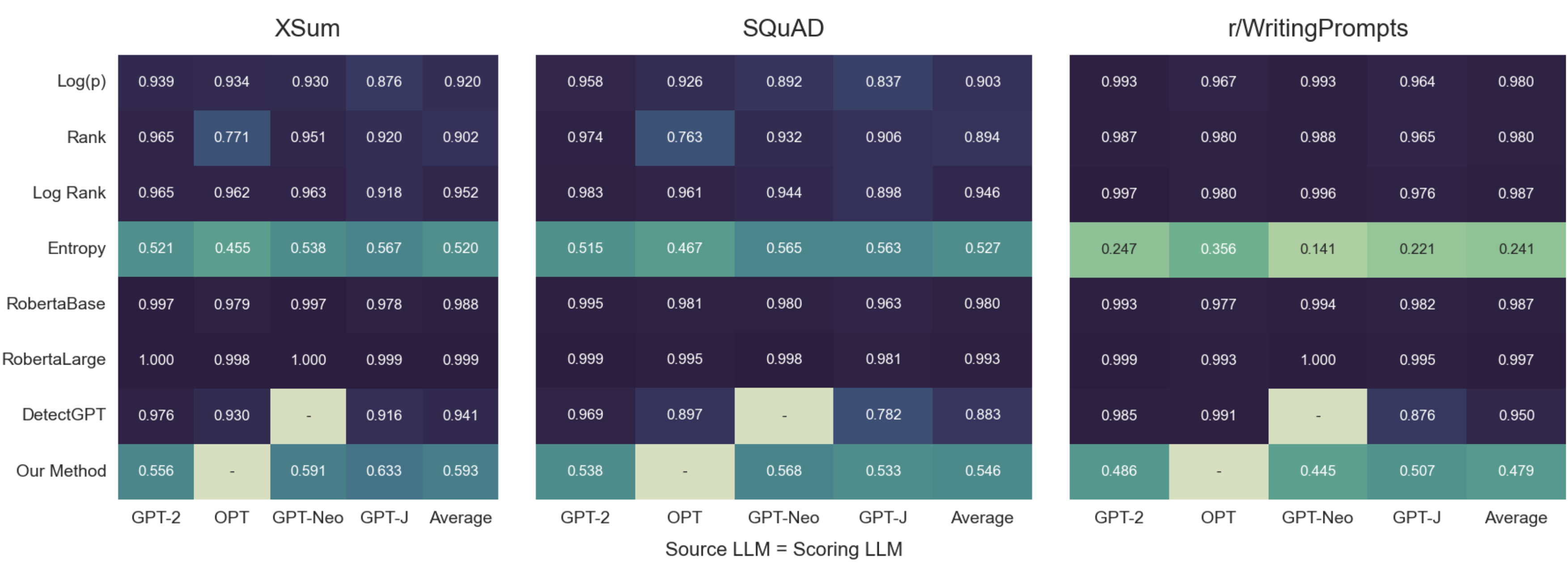

We conducted experiments with the goal of looking for consistent differences between \(\sigma^2_{Z,human}, \sigma^2_{Z,LLM}.\) If our hypothesis is true, we can perform thresholding on $\sigma^2_{Z}$ of any given text, and we will have a competitive AUROC. For comparison, we also ran baseline experiments of other existing methods (the aforementioned zero-shot techniques and DetectGPT) as well as a supervised method (Roberta fine-tuned for text classification, (Liu et al., 2019)).

5.1. Data

For our experiments, we used 200 news articles from XSum (Narayan et al., 2018), 200 Wikipedia excerpts from SQuAD (Rajpurkar et al., 2016), and 200 prompted stories from Reddit WritingPrompts (Fan et al., 2018), the three datasets DetectGPT was also evaluated on.

To generate LLM-written texts for each of these data-points, we took either the first 30 tokens of the human-written text (or, in the case of WritingPrompts, simply the story prompt), prepended an instruction to it - “Write a story based on this prompt.” - and called that our context. We take the LLM-generated tokens that came as a responses to our context as the LLM-generated text. We then removed the context from the original human sample and called that our human-generated text. There was filtering such that each story was at least about 250 words, for a total of 600 stories across the datasets.

5.2. Evaluation Method

The evaluation method is simply the AUROC metric, which is the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curve is a graphical representation of the trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the False Positive Rate (FPR) for different thresholds of a classification model.

To see how our technique measures up to existing zero-shot and supervised learning techniques, we compute AUROCs for benchmark methods including the zero-shot DetectGPT and the supervised learning technique using RobertaLarge. For the zero-shot methods, we simply focused on experiments where the text-generating LLM (source LLM) is the same as the text-scoring LLM (scoring LLM)

Additionally, to compare the relative performance between using the same scoring LLM as the source LLM, as opposed to not, between our technique and our baseline (DetectGPT), we compute:

- AUROC for our method for every scorer-source pair in the set of models that include

gpt2-xl,gpt-j, andgpt-neo, for every dataset (XSum, SQuAD, WritingPrompts), and averaged the AUROCs. This gives us a 3x3 grid of AUROCs representing our approach’s performance on every combination of text-generating LLM and text-scoring LLM.

Note that the AUROCs averaged this way is the same as averaging the AUROCs across the superset of our training data since each dataset has the same number of samples). - We do the same for DetectGPT’s method on our data to serve as a benchmark.

- AUROC for our method for every scorer-source pair in the set of models that include

5.3. Results

For the first point above, we see that our method gives very weak performance relative to other zero-shot learning methods, many of which have average AUROCs \(> 0.90\) for all three datasets. Furthermore, the supervised learning detection models RobertaBase and RobertaLarge performed extremely well on the data, the latter having an average AUROC \(> 0.99\) on all three datasets.

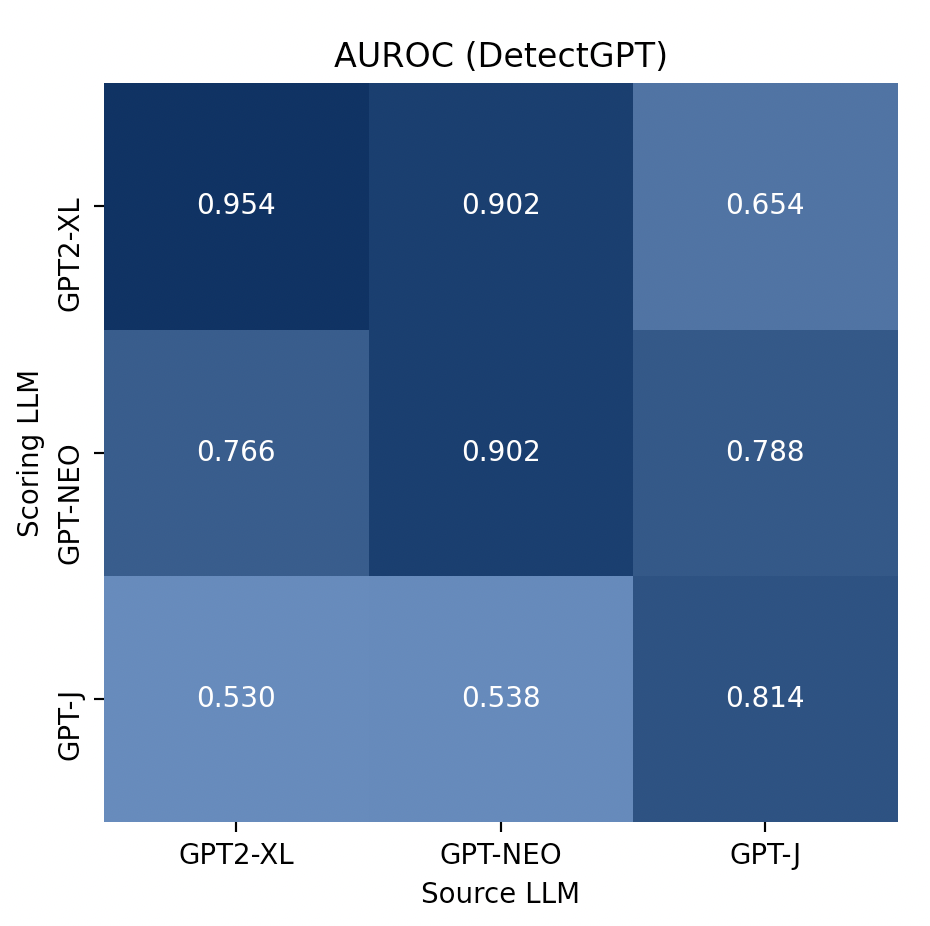

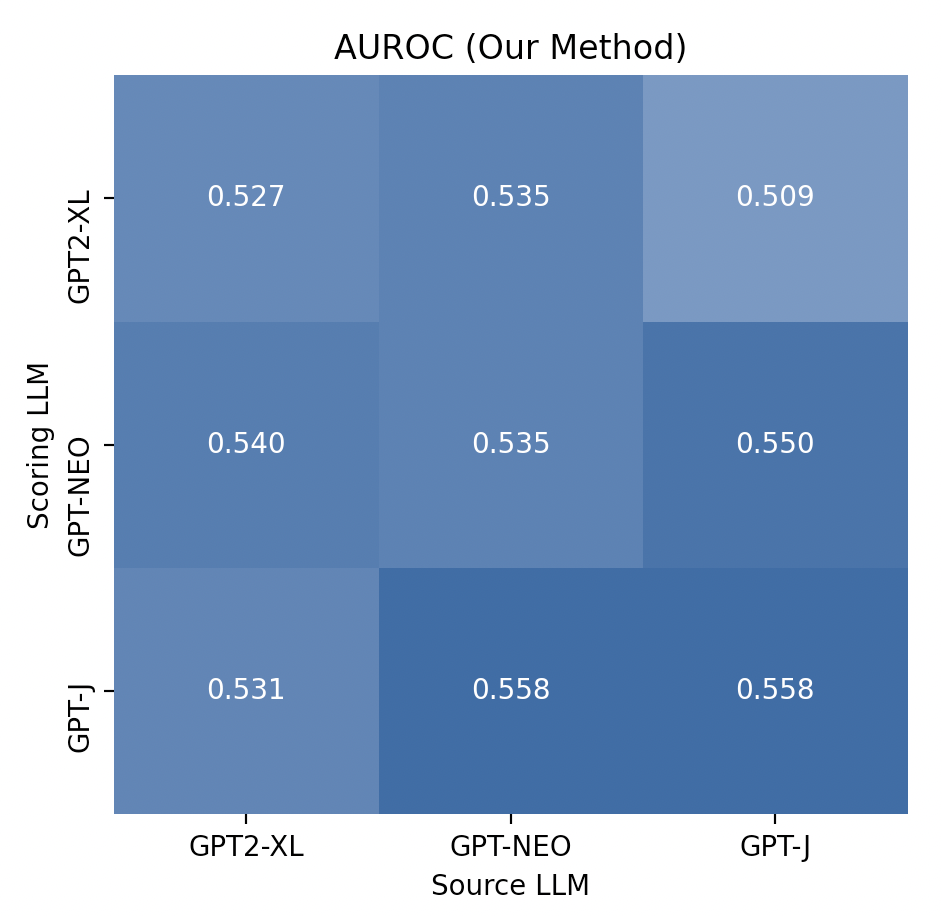

For the second point above, we present the two 3x3 grids:

Note: The 3x3 grid corresponding to the DetectGPT method on our data reports lower AUROCs than reported by the original authors in their paper. This is mainly due to truncated text lengths.

The grids above illustrates that our method achieves low AUROC, but that the AUROC does not decay drastically in cross-model scenarios (off-diagonals) the way it does for the grid corresponding to DetectGPT’s method. At times, we find that our method beats DetectGPT’s performance (e.g. gpt-j scoring gpt-neo-generated or gpt2-xl-generated texts), showing that there is value in using a “second-order approach” to eliminate the reliance on having access to the source LLM. However, this is not sufficiently meaningful of an improvement as the performance is too close to chance.

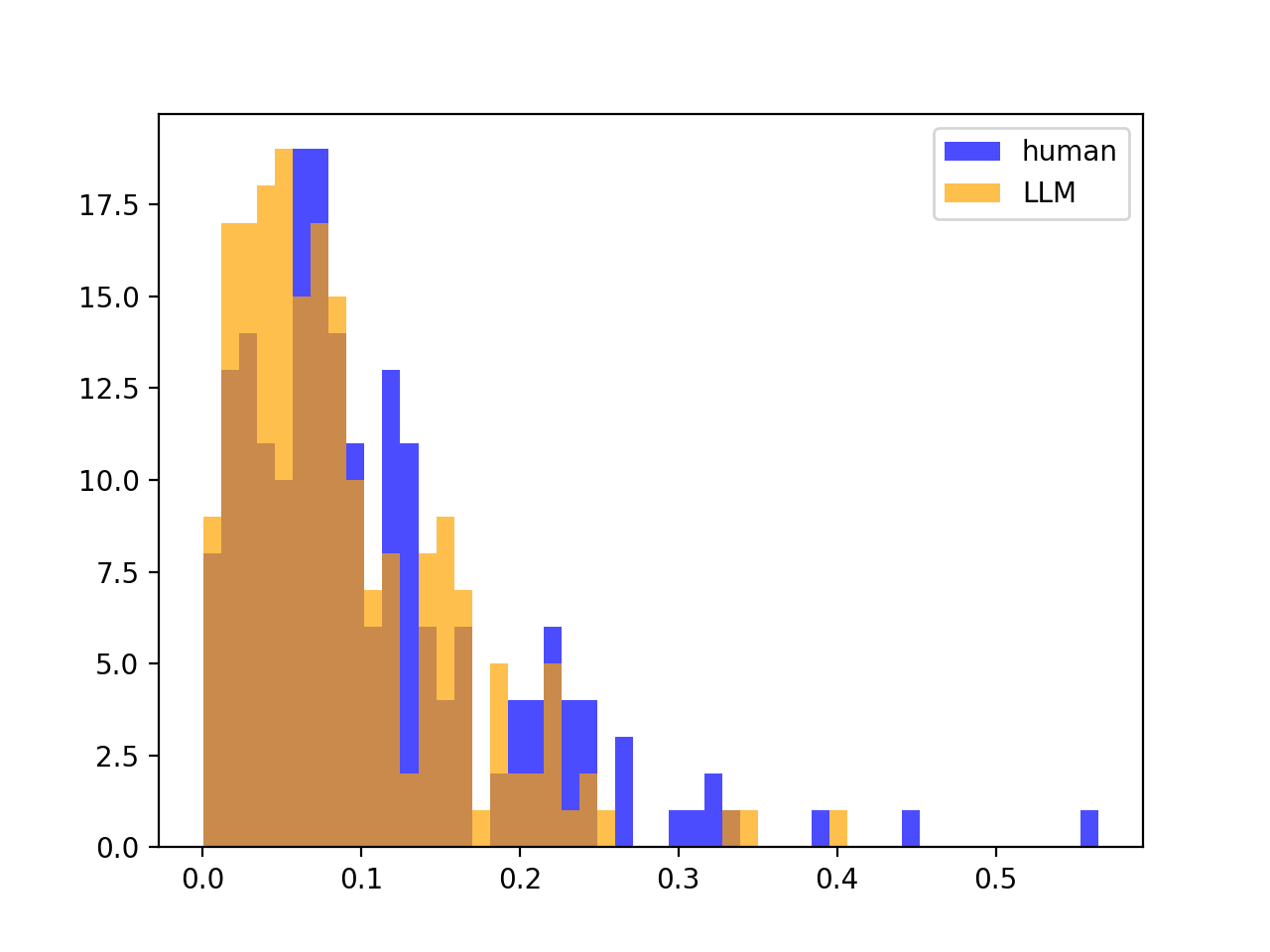

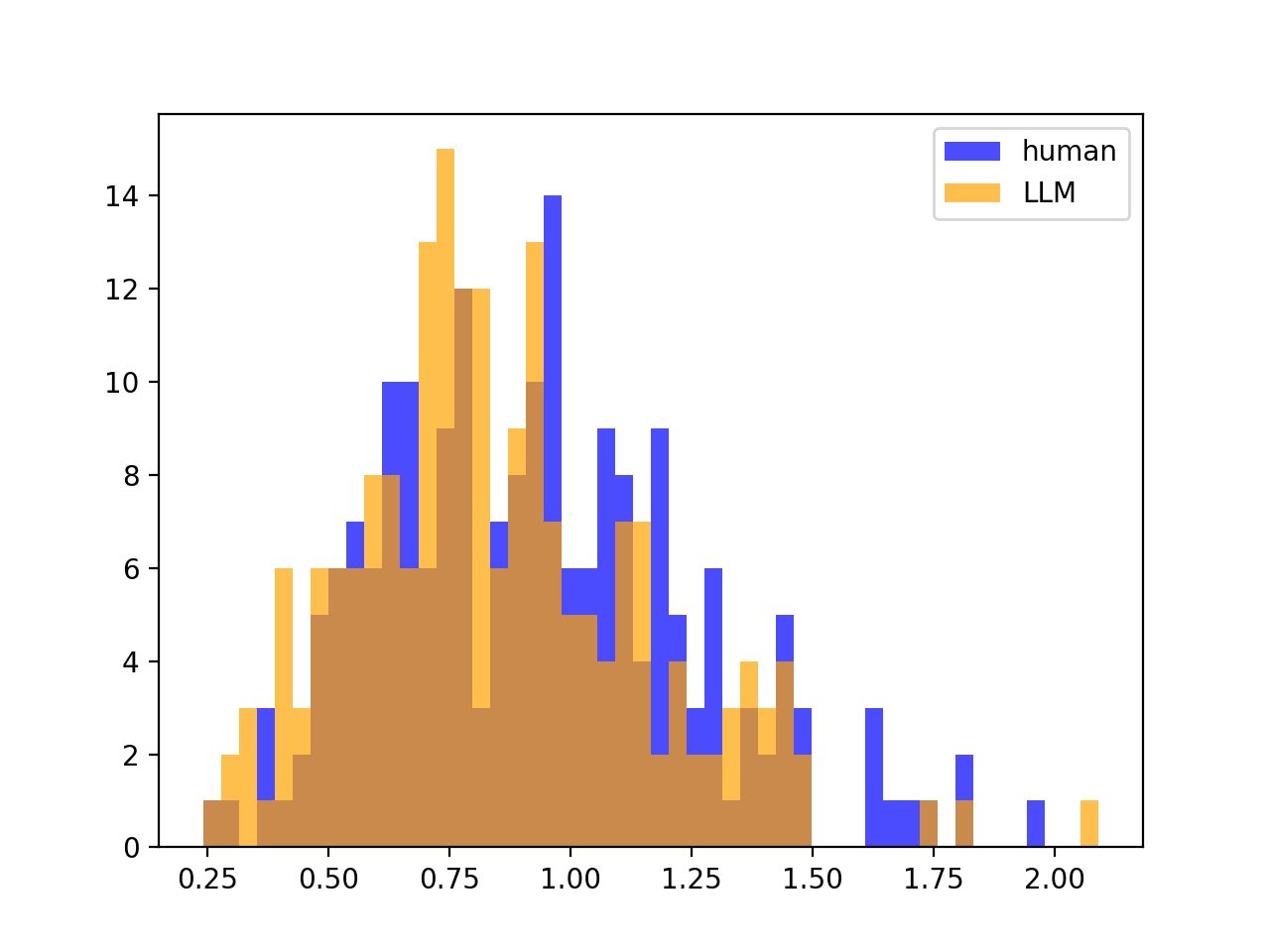

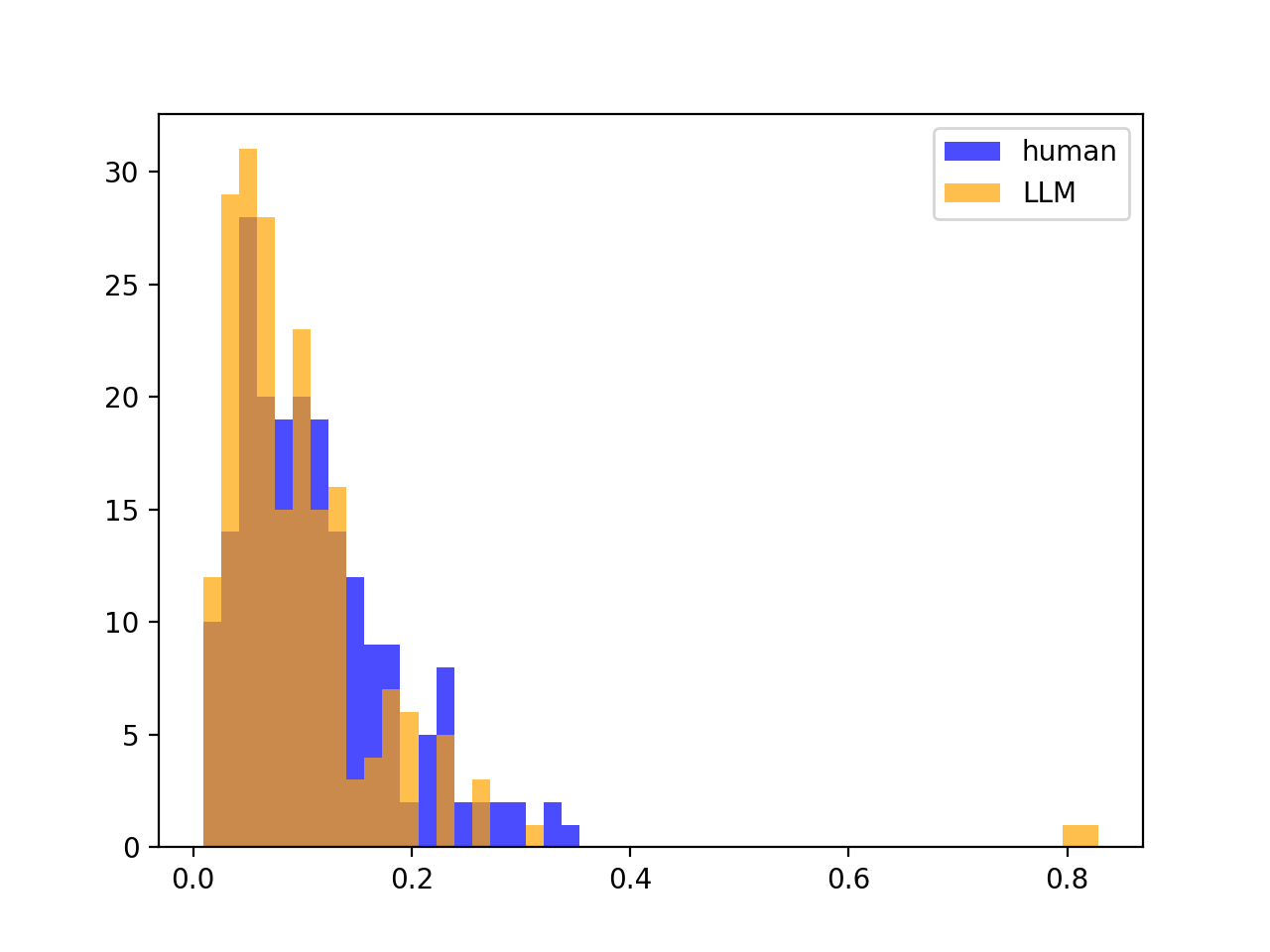

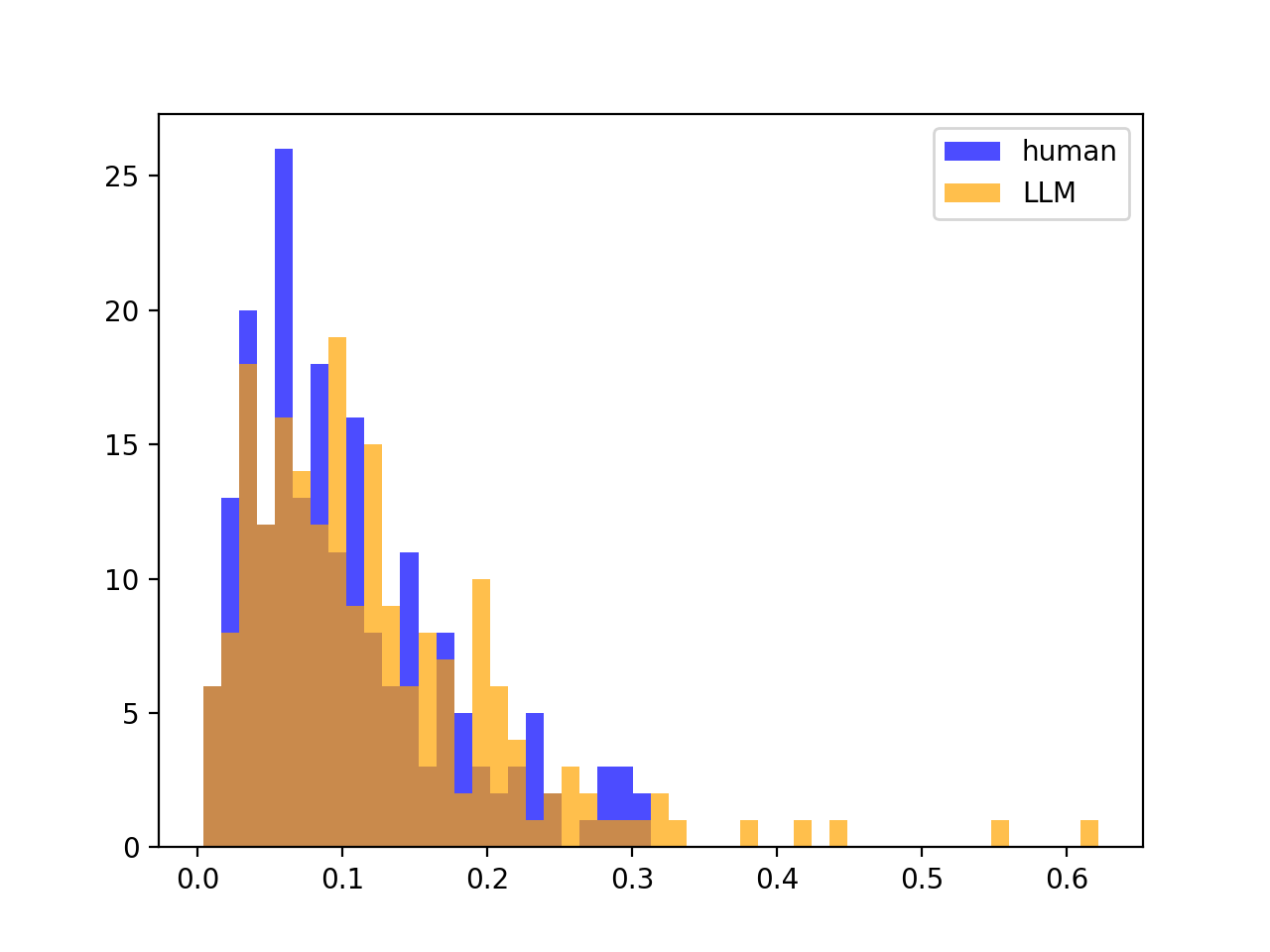

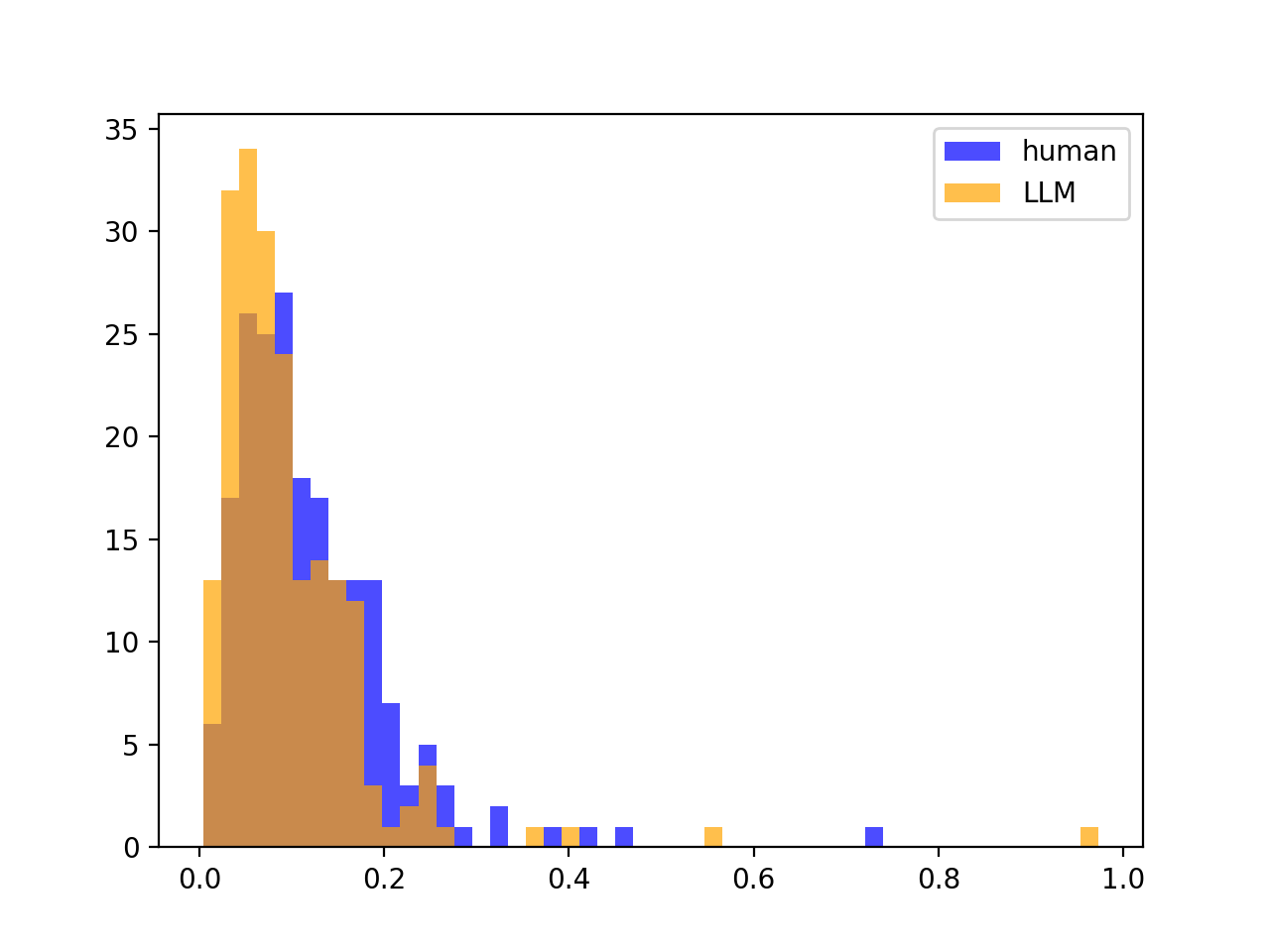

5.5. No distribution Split between \(\sigma^2_{Z, human}, \sigma^2_{Z, LLM}\)

We found that the reason our method is not performative is the lack of a distribution split between \(\sigma^2_{Z,human}\) and \(\sigma^2_{Z,LLM}\), which we find very surprising. For example, below are the distributions of \(\sigma^2_{Z,human}\) and \(\sigma^2_{Z,LLM}\) for $200$ stories from the SQuAD dataset. We find this to be typical of all source LLM - scoring LLM pairings and datasets. We explain this in greater detail and compare this to DetectGPT’s method in the Appendix at the end.

6. Analysis

6.1. Overal Insights

Our results clearly illustrate that there is perhaps not much signal to be gleaned from the variance of partition-wise Z-scores of a piece of text. While we find it hard to believe that, in colloquial terms, humans write with consistent “GPT-2-ness” (or “GPT-Neo-ness” or “GPT-J-ness”) over the whole length of the text, in that our “GPT-2-ness” doesn’t vary too much over the whole text, the statistical experiment we’ve run demonstrates that this is indeed the case.

6.2. Alternative Attempts

6.2.1 Other Statistical Measures

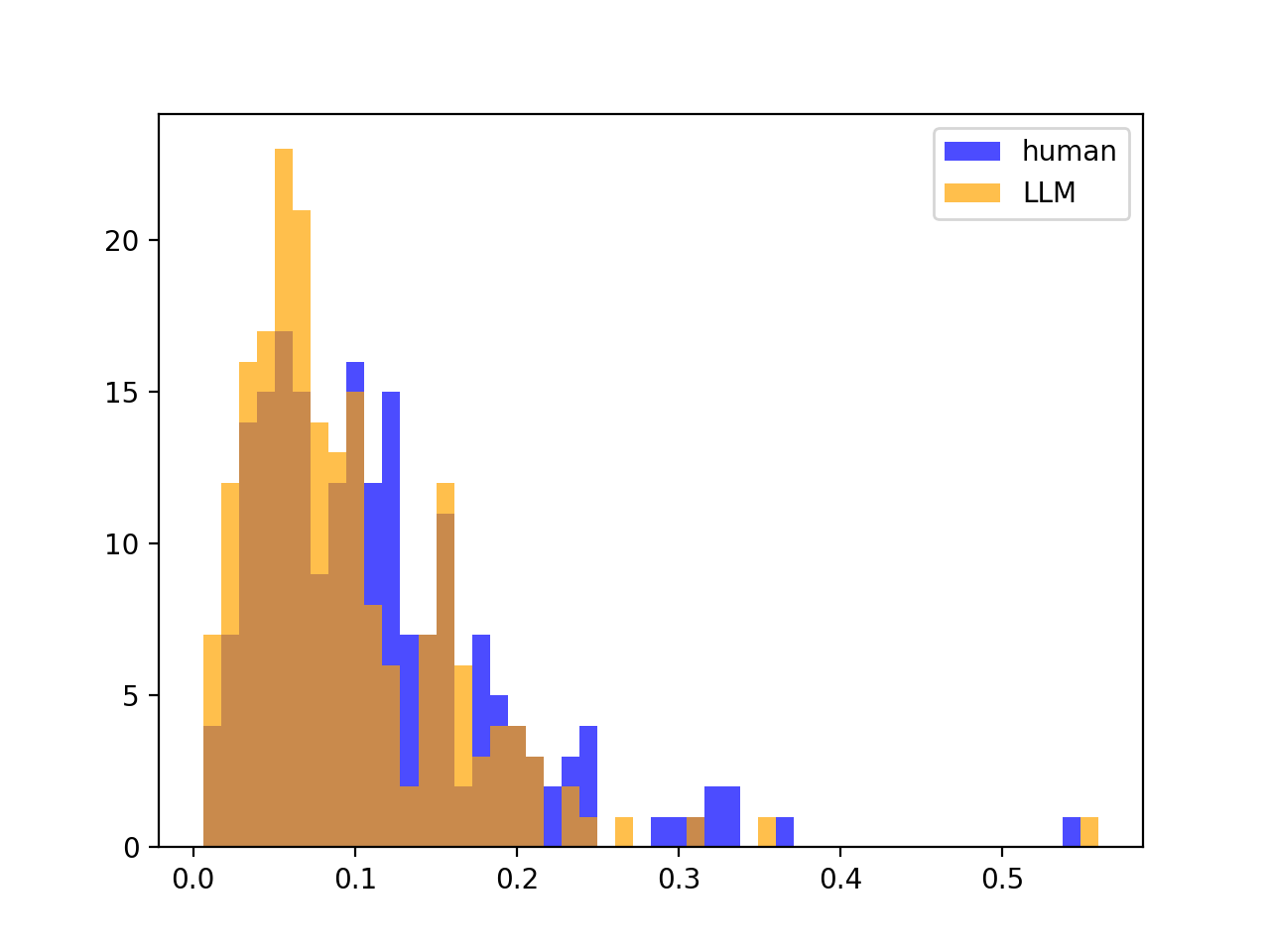

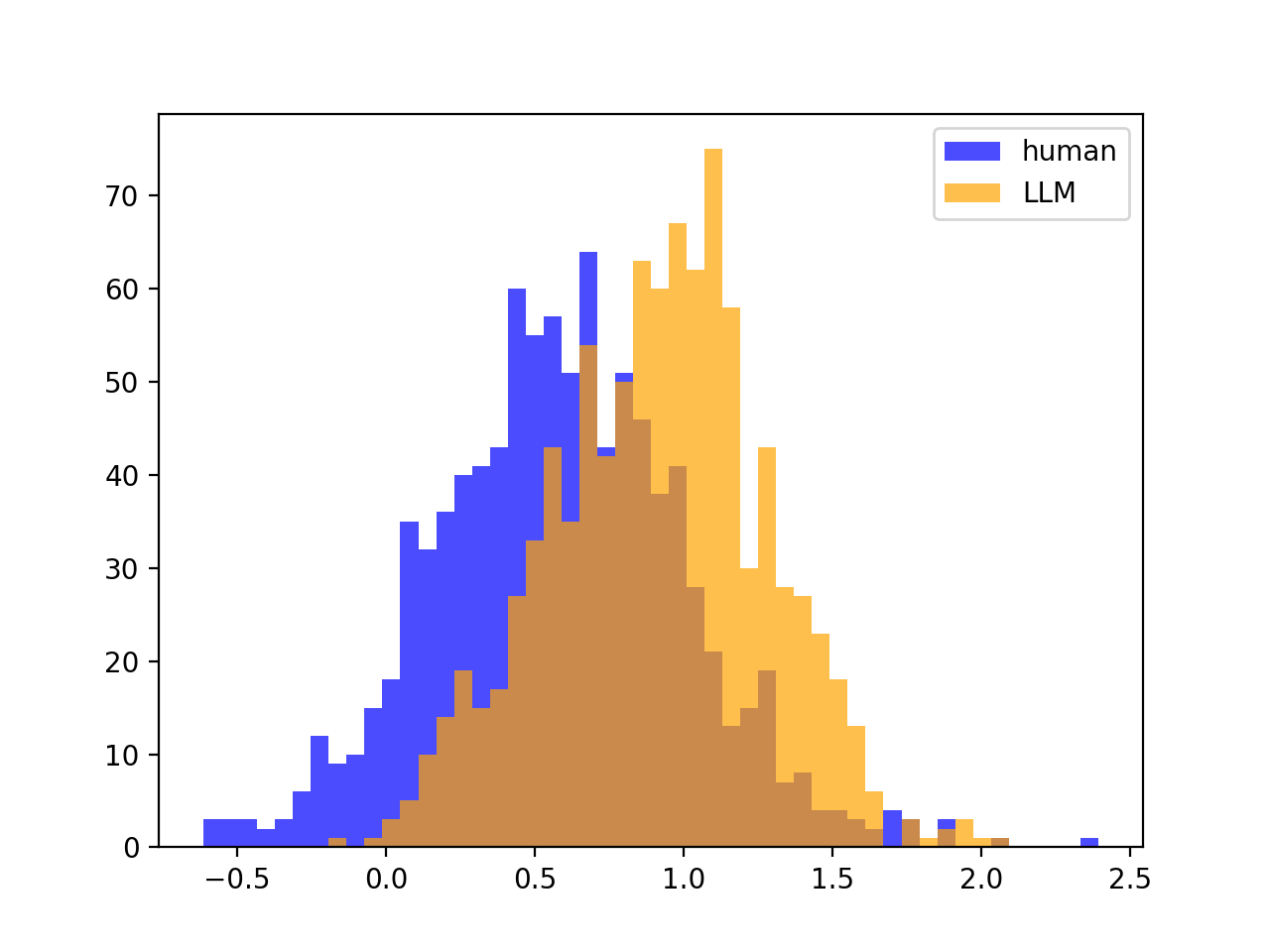

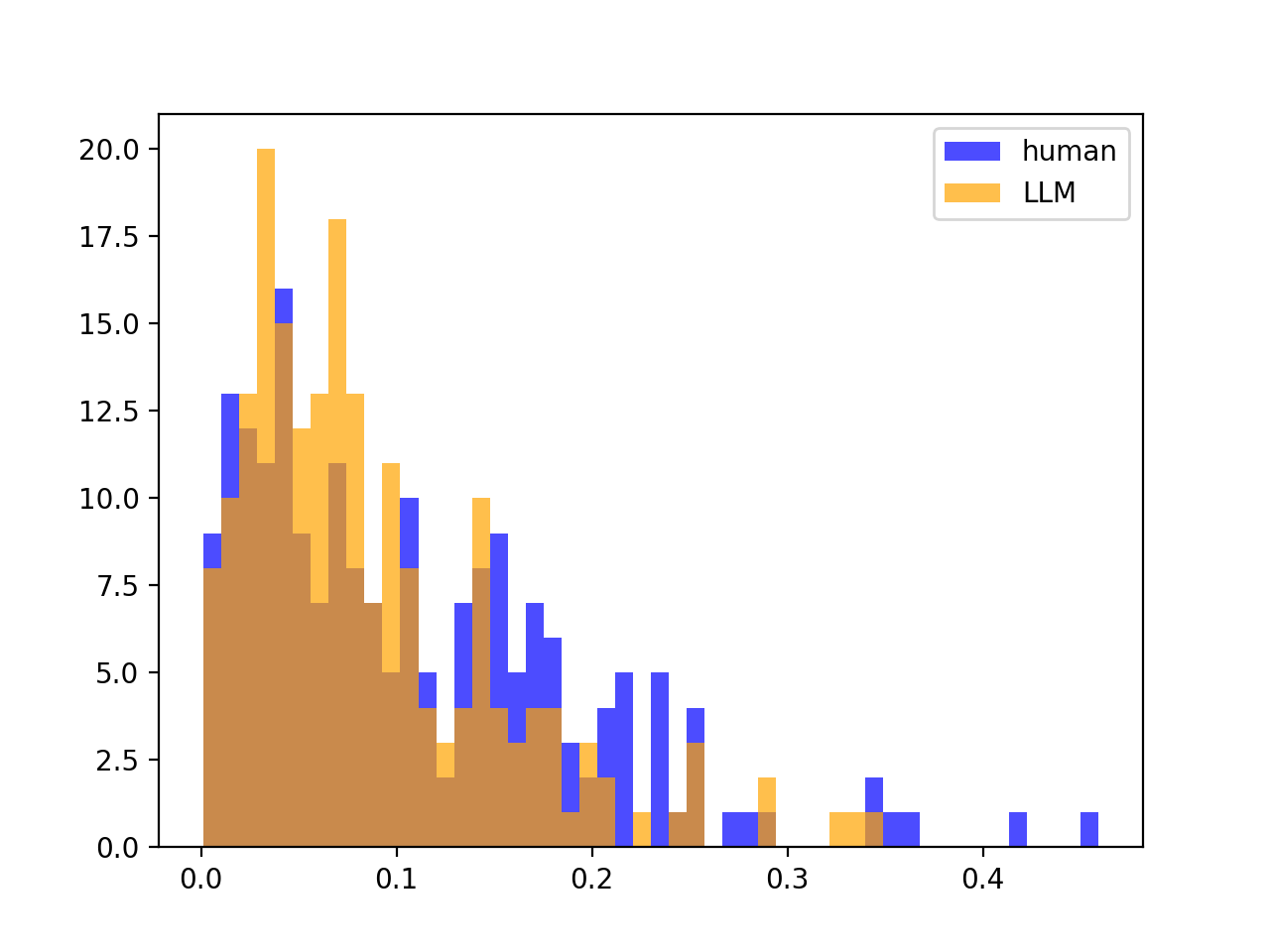

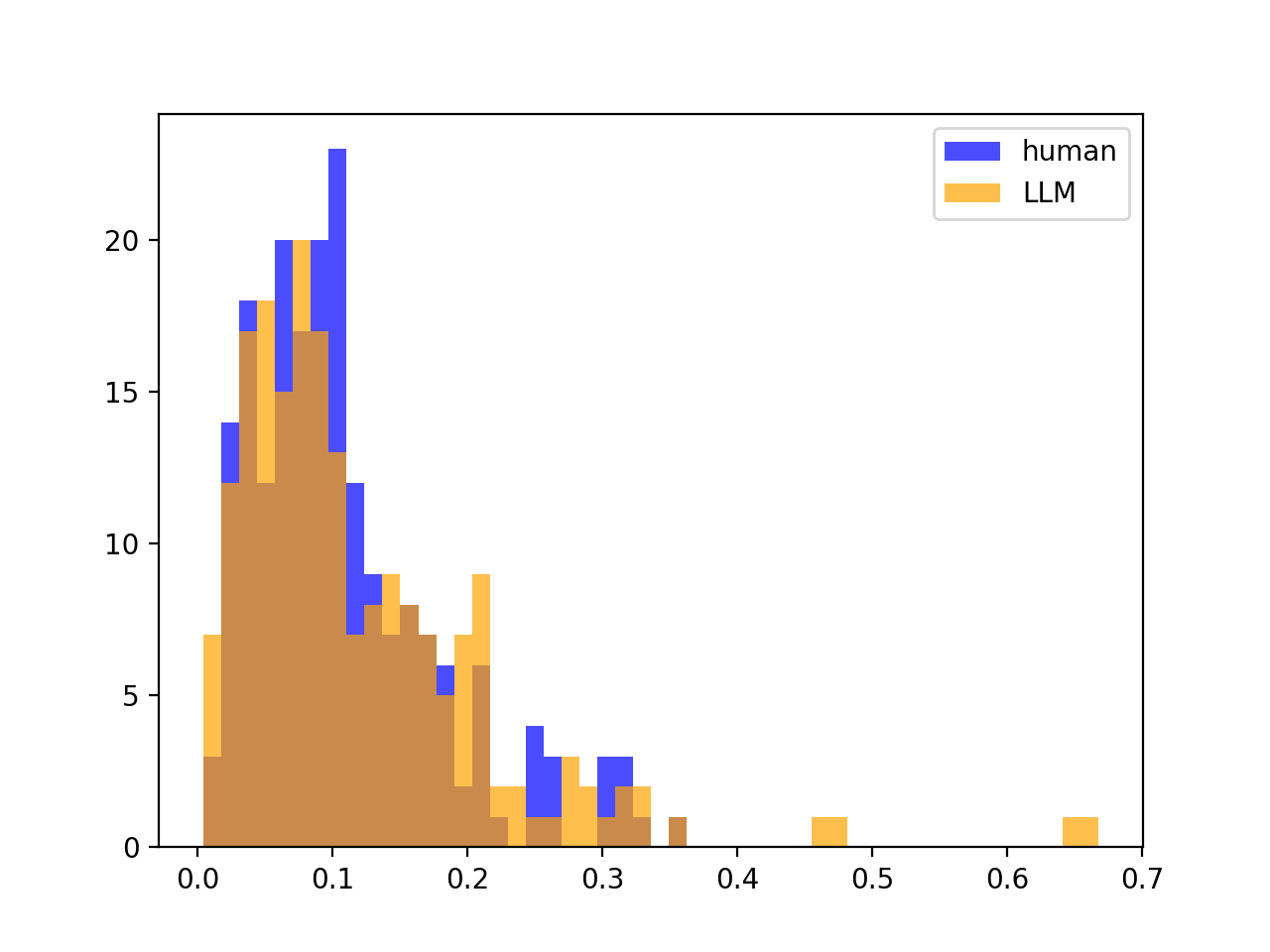

We also tried looking at various statistical measures instead of \(\sigma^2_Z\). A notable example is to use \(\max_\text{segments in text}(Z) − \min_\text{segments in text}(Z)\), what we call the Z-span of a text, but reasoned that the extra few AUROC points gained do not outweigh the added susceptibility to outliers. That said, outlier susceptibility could be a desirable feature in another similar approach, as outliers could indicate the presence of more than one author; that is outside the scope of this paper. As a comparison, we illustrate the distributions of \(\sigma^2_Z\) (left) versus Z-span (right):

Though the two metrics look distributionally different (seemingly log-normal versus binomial), it does not impact the separation between the LLM and human distributions.

6.2.2. Other Parameters

Our initial small-scale Proof-Of-Concept experiment (that indicated there was a distribution separation between \(\sigma^2_{Z, human}, \sigma^2_{Z, LLM}\)) used slightly different parameters, which had all to do with segment size. We used a segment size of $30$ instead of $50$, but reason that that cannot be the reason the initial experiment appeared successful while the full-scale experiment showed otherwise. The reason for this is that even if segment size had an effect on \(\sigma^2_Z\), the nature of this being a simple statistical measure means that we can prove that \(\sigma^2_Z\) decays exponentially with segment size. The distribution separation visible with a segment size of $50$ should be non-zero iff it is non-zero with a segment size of $30$, only smaller.

The only way this can be false is if the distribution of \(\sigma^2_Z\) is somewhat more exotic, such as being a bimodal distribution, which we reason as being extremely unlikely, given the success of other techniques that hinge on many Gaussian assumptions.

7. Conclusion / Future Work

Though our method does not offer a compelling solution to the model-agnostic zero-shot text-detection problem, we were nonetheless able to statistically study LLM-generated and human-generated texts and arrive at a very surprising result.

We reiterate that even though supervised detectors may seem to be an attractive solution, as LLMs proliferate, we have less and less control over the factors that significantly impact the performance of such solutions, or even the design of one, such as training data skews, model class, and compute. Statistical analysis of LLM likelihood functions seems to be a promising avenue of research that could arrive at second-order solutions that circumvent these model dependencies.

As future work, we note that in exploring our approach, we observe the impact of the LLM likelihood function (and by extension, its sampling strategies) on our ability to design discriminators. These include the hyperparameters of nucleus-sampling, beam-search, and so on, that were out of scope of this project to fine-tune. However, there is good reason to believe that research on how they may be used to create a good discriminating strategy could be fruitful. Another avenue to continue exploration is to investigate the impact of text length. While it is intuitive that longer text lengths will increase the discriminating power of any detector, it is not statistically clear that it is true.

8. Appendix

We present a bunch of plots that we hope clearly explain the failure modes of DetectGPT and our method.

8.1. DetectGPT’s success and failure mode

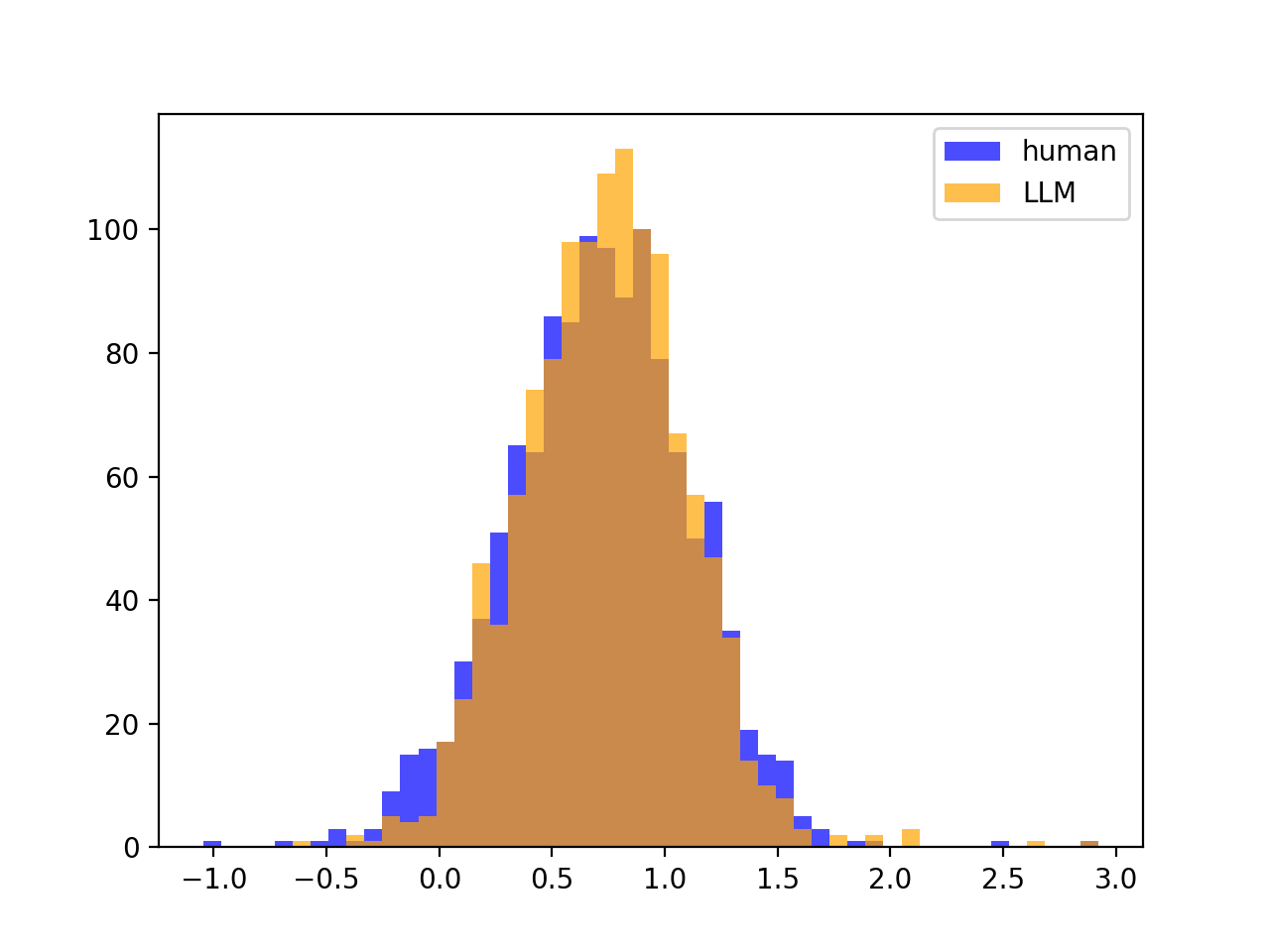

Recall that DetectGPT’s method involves generating perturbations of entire texts and comparing the log-likelihood of the original unperturbed text to the distribution of log-likelihoods of the perturbations. If the text was machine-written, the original text’s log-likelihood will have a high Z-score relative to the distribution. If it was human-written, it will have only a moderate Z-score.

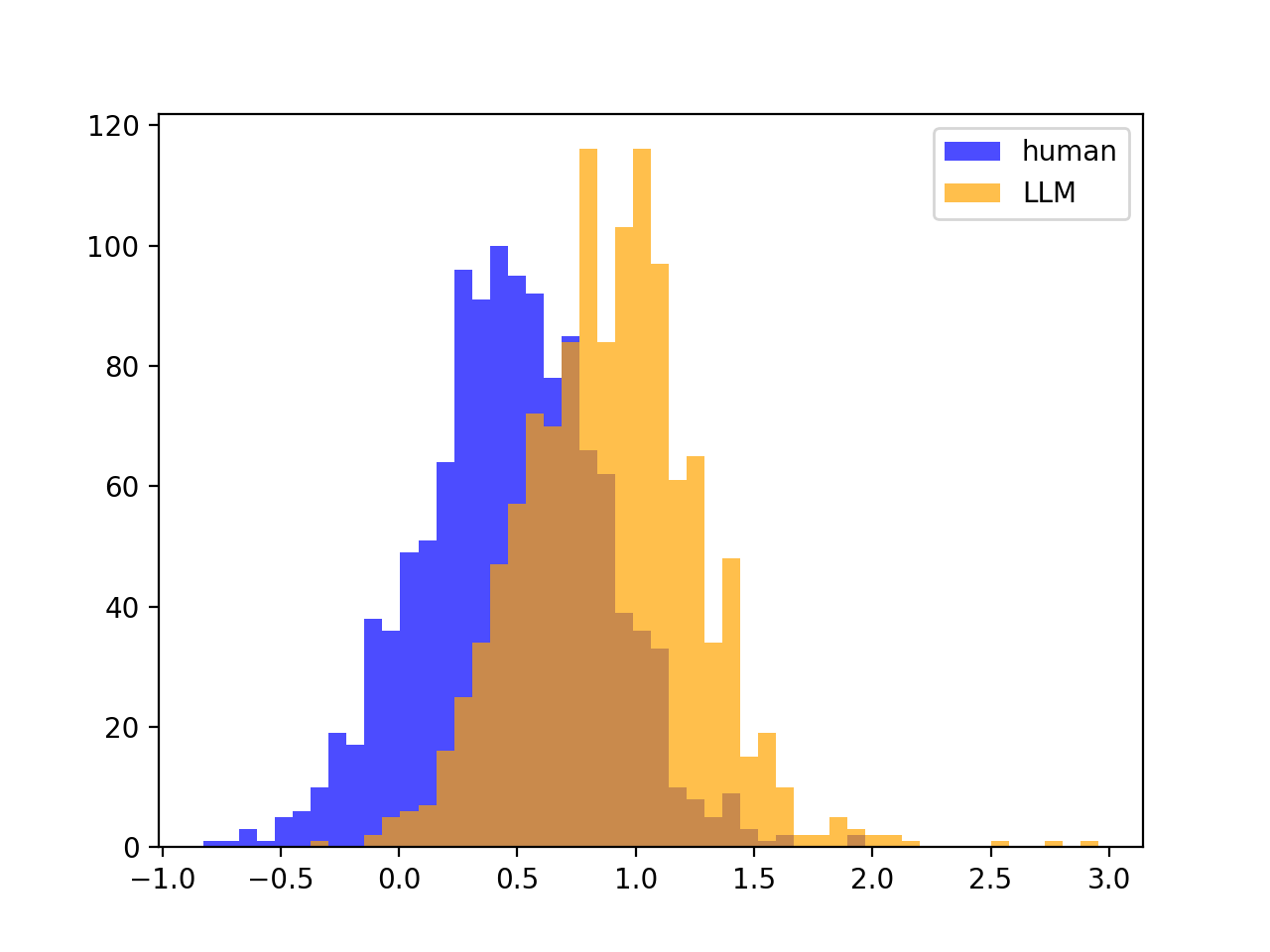

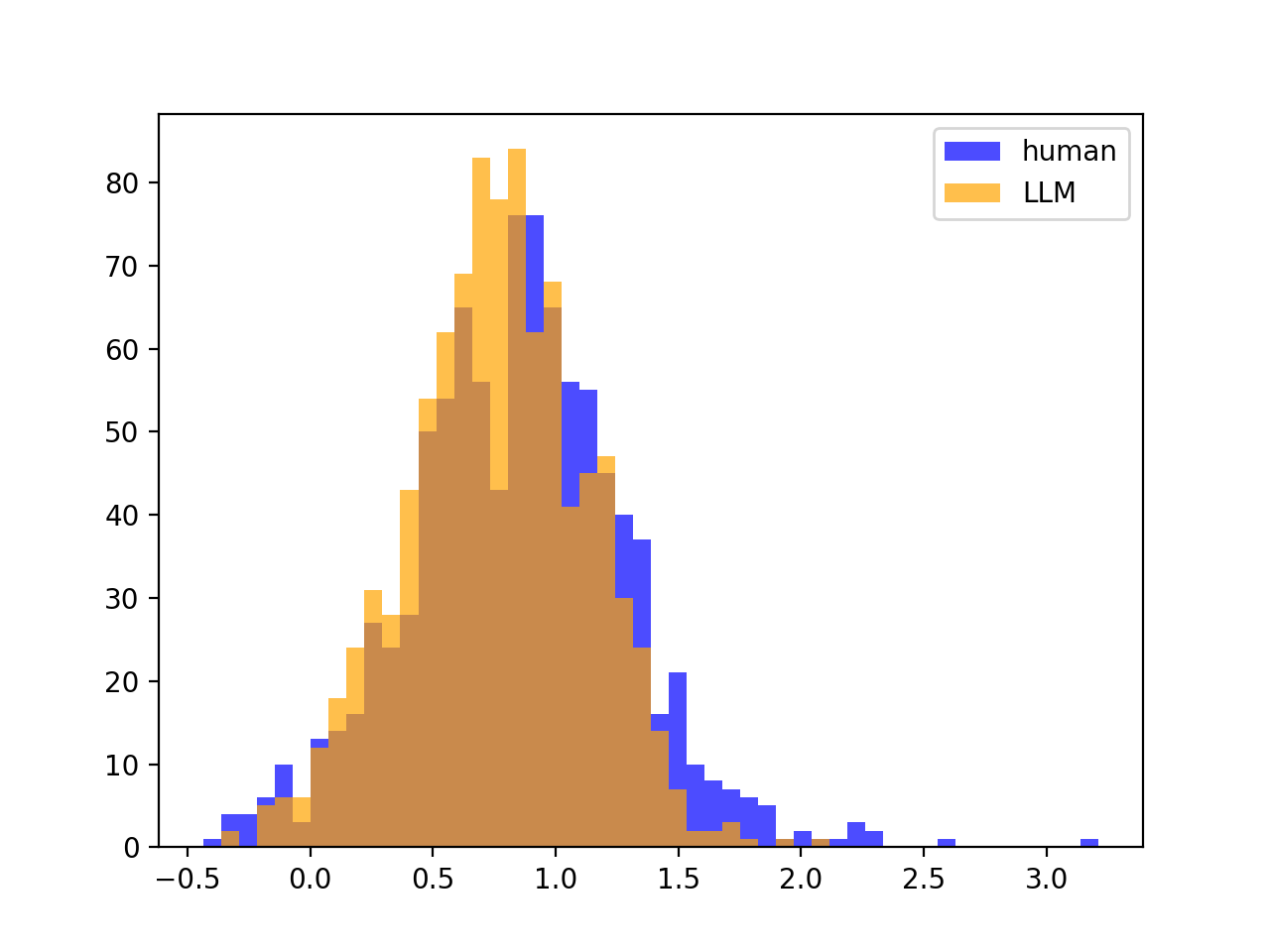

If source LLM $=$ scoring LLM, then the split is clear between the Z-scores, meaning that DetectGPT will work. For example, if we look at gpt-neo-2.7B scoring gpt-neo-2.7B paritions / text, we have nicely seperated Z-score distributions:

But, the variances of the Z-scores look the same between human and LLM (no split, as mentioned):

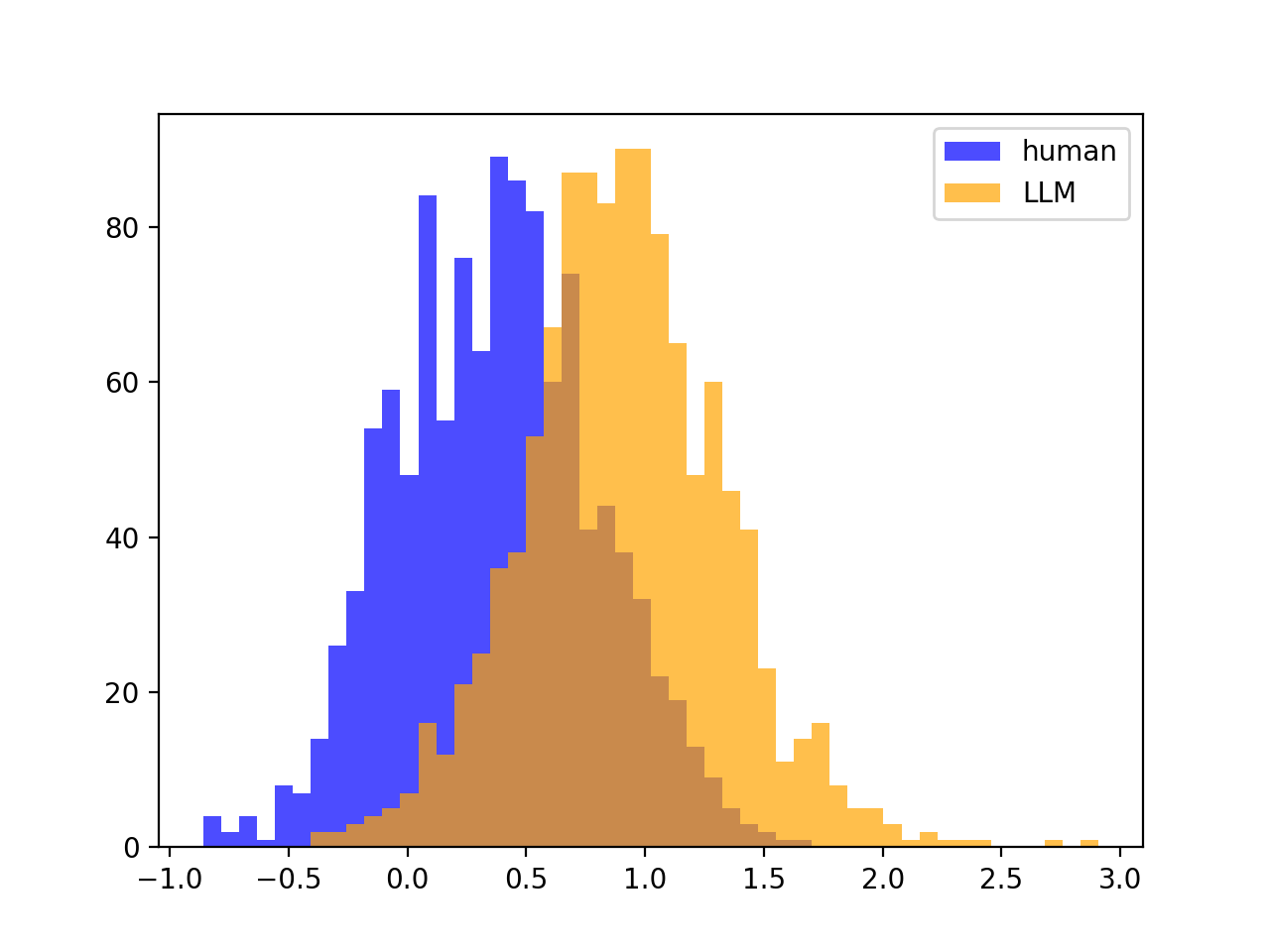

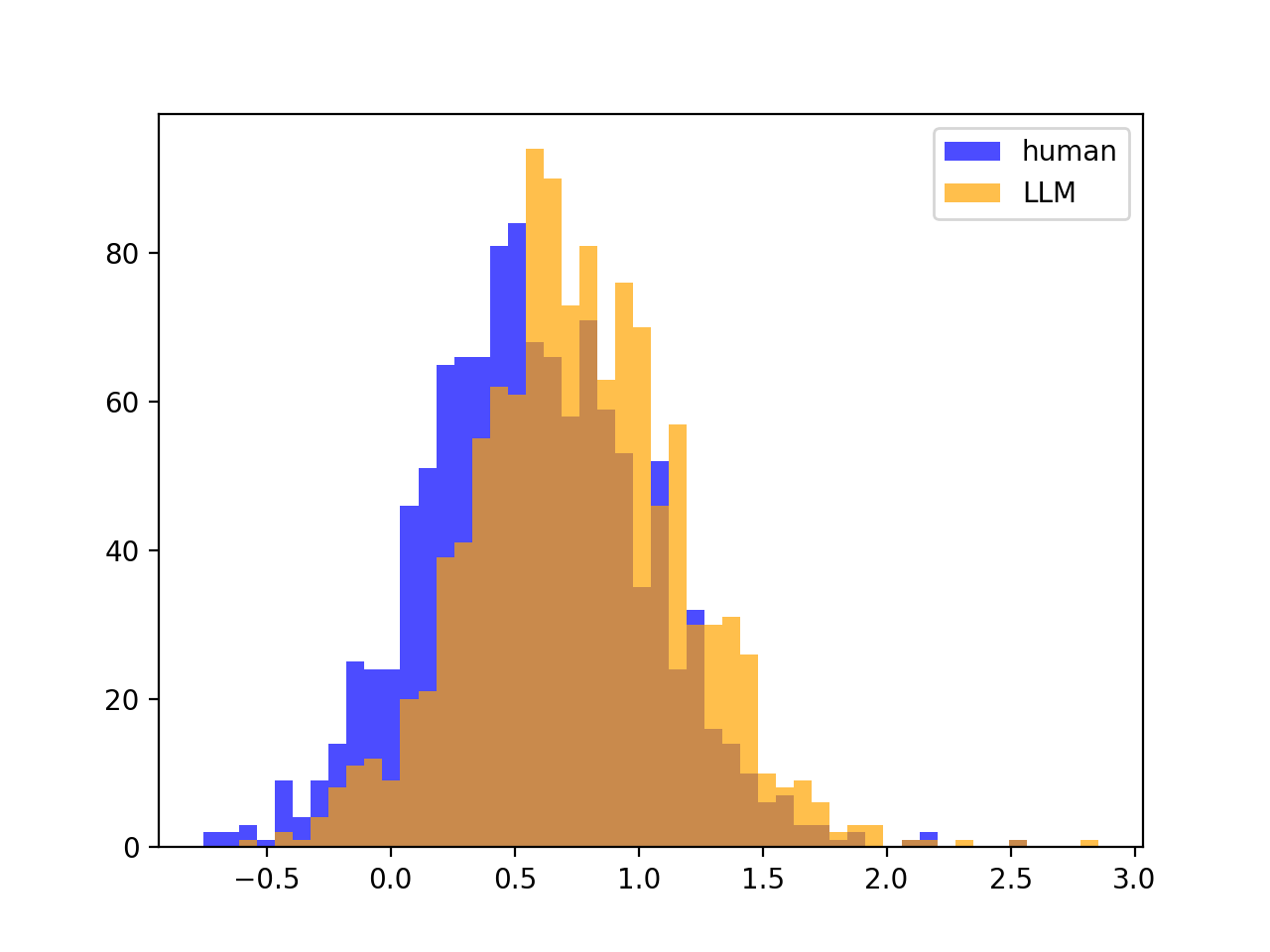

However, if source LLM $\neq$ scoring LLM, there is often no split, meaning that DetectGPT often will not work. For example, if we look at gpt-j-6B scoring gpt-neo-2.7B partitions / text:

Variances of Z-scores looks the same as before; no split:

9. References

Angela Fan, Mike Lewis, and Yann Dauphin. 2018. Hierarchical neural story generation. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 889–898, Melbourne, Australia. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Sebastian Gehrmann, Hendrik Strobelt, and Alexander Rush. 2019. GLTR: Statistical detection and visualization of generated text. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, pages 111–116, Florence, Italy. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Daphne Ippolito, Daniel Duckworth, Chris Callison-Burch, and Douglas Eck. 2020. Automatic detection of generated text is easiest when humans are fooled. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 1808–1822, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. 2019. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach.

Eric Mitchell, Yoonho Lee, Alexander Khazatsky, Christopher D. Manning, and Chelsea Finn. 2023. Detectgpt: Zero-shot machine-generated text detection using probability curvature.

Shashi Narayan, Shay B. Cohen, and Mirella Lapata. 2018. Don’t give me the details, just the summary! topic-aware convolutional neural networks for extreme summarization. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1797–1807, Brussels, Belgium. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. 2016. SQuAD: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2383–2392, Austin, Texas. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Irene Solaiman, Miles Brundage, Jack Clark, Amanda Askell, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Jeff Wu, Alec Radford, Gretchen Krueger, Jong Wook Kim, Sarah Kreps, Miles McCain, Alex Newhouse, Jason Blazakis, Kris McGuffie, and Jasmine Wang. 2019. Release strategies and the social impacts of language models.

- Romal Thoppilan, Daniel De Freitas, Jamie Hall, Noam Shazeer, Apoorv Kulshreshtha, Heng-Tze Cheng, Alicia Jin, Taylor Bos, Leslie Baker, Yu Du, YaGuang Li, Hongrae Lee, Huaixiu Steven Zheng, Amin Ghafouri, Marcelo Menegali, Yanping Huang, Maxim Krikun, Dmitry Lepikhin, James Qin, Dehao Chen, Yuanzhong Xu, Zhifeng Chen, Adam Roberts, Maarten Bosma, Vincent Zhao, Yanqi Zhou, Chung-Ching Chang, Igor Krivokon, Will Rusch, Marc Pickett, Pranesh Srinivasan, Laichee Man, Kathleen Meier-Hellstern, Meredith Ringel Morris, Tulsee Doshi, Renelito Delos Santos, Toju Duke, Johnny Soraker, Ben Zevenbergen, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Mark Diaz, Ben Hutchinson, Kristen Olson, Alejandra Molina, Erin Hoffman-John, Josh Lee, Lora Aroyo, Ravi Rajakumar, Alena Butryna, Matthew Lamm, Viktoriya Kuzmina, Joe Fenton, Aaron Cohen, Rachel Bernstein, Ray Kurzweil, Blaise Aguera-Arcas, Claire Cui, Marian Croak, Ed Chi, and Quoc Le. 2022. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications.